In our consultancy and training sessions over the past few years, we have often been asked questions by European customers or audiences such as:

“Cars like Volkswagen, BMW and Audi are first class in terms of safety. Why are their sales declining in the Chinese market?”

“European household appliances – from refrigerators and washing machines to air purifiers – sell well in Europe but often fail in China. What’s the reason?”

“European power tools are durable and powerful, but they get a cold reception in China. Why is that?”

Although these products are different in terms of category, competition and regulatory requirements, my long-term observations of both European and Chinese markets point to one core issue: a lack of understanding of the consumer logic of the target market. In particular, there’s often insufficient insight into the differences between what I call “chopstick culture” and “fork and knife culture”.

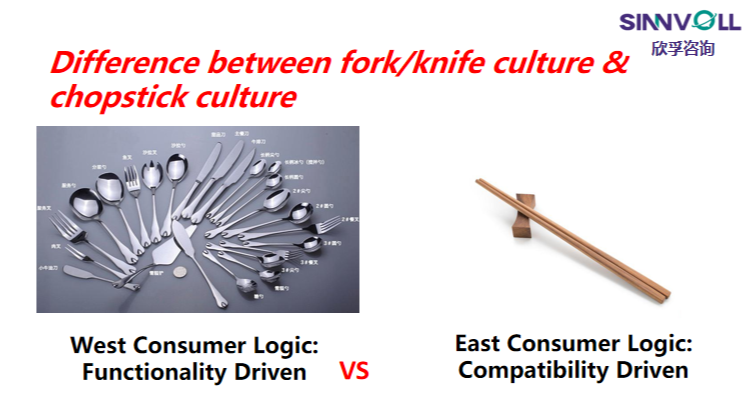

“Chopstick culture” vs. “Fork/knife culture”: How consumer logic differs

The way people think about consumption in Chinese and Western markets is strikingly different. Based on more than a decade of global research and hands-on experience by our team, we can boil it down to a contrast between “Chopsticks Culture” and “Fork/Knife Culture”.

What is fork/knife culture?

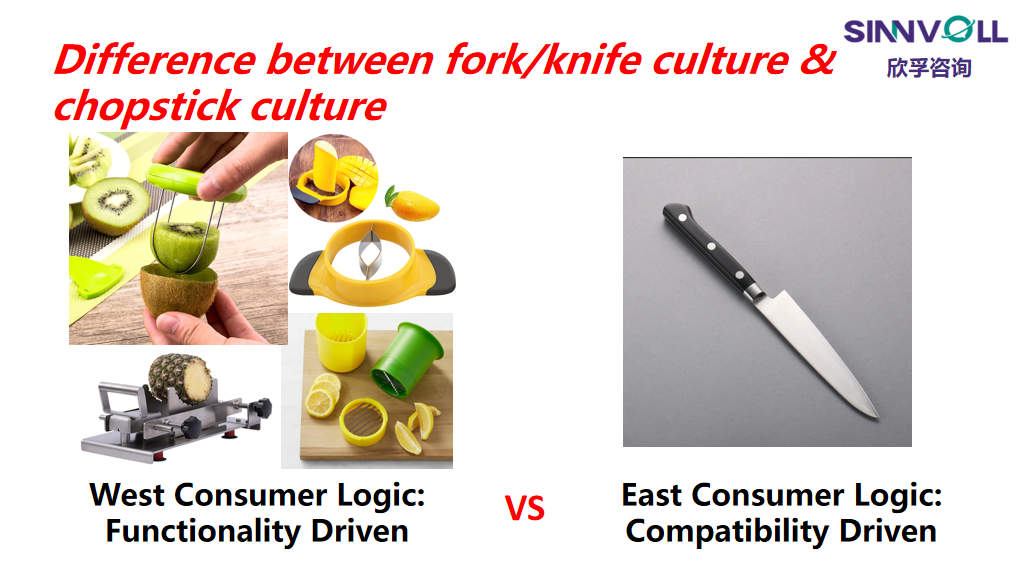

Simply put, fork/knife culture is one tool for one job – a mindset we call function-driven or functionalism. Take French cuisine as an example: a meal might include forks and knives for starters, main courses and fish, as well as soup spoons, dessert spoons and coffee spoons. A person could easily use more than ten utensils in a single sitting. Another clear example is fruit peelers. In China, a single fruit knife can handle almost any fruit. But in middle-class or wealthier homes in Europe and the US, you might find a whole drawer full of specialised tools – one for each type of fruit, some even machine-operated.

Western consumers are happy to pay for these products because they value extreme professionalism: focusing on one thing for a lifetime, with each tool designed for a specific purpose. This is why they use email for work, WhatsApp for family chats, Instagram or TikTok for friends, Uber for rides and PayPal for payments. It’s not that app developers aren’t trying – it’s that consumers prefer tools that shine in a specific situation.

What is “chopsticks culture”?

Let’s turn to the Chinese market, a classic example of “chopsticks culture”. Chinese people – and others in Confucian-influenced countries such as Japan, South Korea, Vietnam and Thailand – rely on a pair of chopsticks for almost everything, perhaps adding a spoon at most. This habit reflects a deep-seated quest for compatibility: getting the most out of the fewest tools with the least effort. So in “chopstick culture” markets, consumers aren’t drawn to products that do just one thing. Instead, sellers work hard to pack multiple functions into a single item.

This is why European products, which often emphasise excellence in one area, can feel out of place in China. Products that come from the “fork and knife culture” simply don’t fit into the “chopstick culture” consumer mindset.

Answering the big questions

To effectively engage with customers, it’s important to have a clear perspective. To succeed in China, manufacturers, retailers and brands need to move beyond a singular focus on issues such as safety or durability. Instead, they need to adopt a broader strategy and tailor their products to meet a range of everyday needs of Chinese consumers.

As consumers begin to view cars not only as a means of transportation, but also as an entertainment space or a mobile living room, brands must find ways to meet these multifaceted expectations. Simply highlighting safety features is not enough, as this is not the primary motivation for their purchase decisions. If brands fail to adapt in this way, local competitors may seize the opportunity, and by the time this realisation sets in, it may be too late to respond effectively.

Of course, adding features isn’t always easy. It requires not only a solid grasp of market trends, but also an accurate understanding of who consumers are and what they want.

In short, foreign companies targeting the Chinese market need to deeply understand the divide between ‘chopstick culture’ and ‘fork/knife culture’. They need to shift their thinking from piling on features to pinpointing exactly what fits the market. Only then can they unlock the full potential of the Chinese market and make real progress in their overseas growth.