The journey of Chinese companies in India will undoubtedly be full of risks and challenges Nevertheless, for enterprises demonstrating genuine courage and foresight, the immaturity and uncertainty of the Indian market represent only one side of the coin. On the other side, this presents a significant opportunity for business growth and expansion. It seems reasonable to posit that, in the near future, India, despite having deterred numerous foreign companies, could evolve into a platform for the growth and expansion of a few Chinese enterprises.

There are indications that India is undergoing a period of accelerated growth and development.

On 23 August, India became the fourth country in history to successfully land a rover on the Moon. This event marks a significant moment in the country’s history, indicating a new era for a country that has often been viewed as chaotic and impoverished.

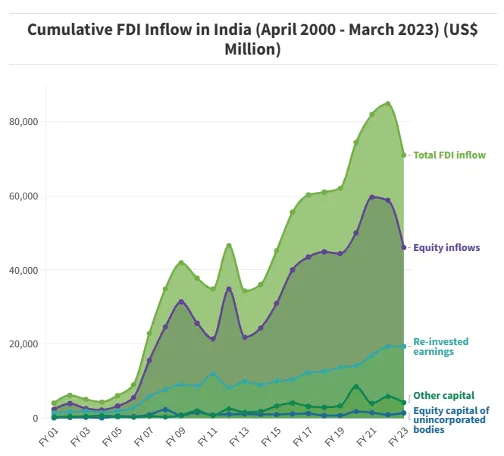

Indeed, not only India’s space programme is advancing at a rapid pace, but also its overall national strength has seen substantial growth in recent years. In terms of population, India is sitting at the top of the world and will be unrivaled for the next half century. From an economic standpoint, India is benefiting from the global trend of derisking, attracting foreign investments that are relocating their industrial chains to the country. The International Monetary Fund (IMF) has forecast that by 2023, India will be the fastest-growing major economy worldwide. In terms of military, India is consistently increasing its budgetary allocation for defence, thereby positioning itself as the third-largest defence spender globally, behind China and the United States.

The notion of India potentially becoming a superpower is currently the subject of much discussion. Those of Indian elite status are proclaiming with great enthusiasm that the 21st century will unquestionably be India’s century.

Concurrently, India’s foreign policy has become increasingly hawkish. From a geopolitical perspective, India is engaged in intensifying interactions with Europe, the United States, and Japan. In June, Modi and Biden released a joint statement in which they described US-India relations as the defining partnership of this century. Leaders from Germany, the United Kingdom, Australia, and Japan have each paid a visit to India. India and the Western world are increasingly cooperating in areas ranging from trade to diplomacy to security. The objective of this India is to secure advantageous positions in international relations through global strategic initiatives.

The changes in India present a dual scenario of opportunities and challenges for Chinese companies. While there is a clear indication of emerging market opportunities, incidents such as the freezing of funds belonging to Xiaomi have given rise to concerns. In this complex market environment and challenging macroeconomic landscape, Chinese enterprises in the Indian market how to layout, is a long-term preparation, waiting for the opportunity to invest or stop and leave the field?

This article, based on research and tracking conducted by the Global Localization Research Team of Sinnvoll Consultancy, aims to provide a comprehensive analysis of the risks and opportunities in the Indian market from three distinct perspectives: Indian Market: Are there more opportunities or risks, Investment in India: Is it a paradise or a graveyard for foreign investments, Do Chinese companies still have opportunities in India?

Our aim is to offer neutral, objective, and constructive insights and advice for business decision-makers.

Indian Market: Are there more opportunities or risks?

Simply put, the characteristics of the Indian market can be summarized as “three fast, three slow”.

Firstly, the population is growing fast in India. With a considerable proportion of the population comprising young people, approximately one in every five individuals under the age of 25 globally is Indian. By the first half of 2023, India’s population had reached 1.41 billion, exceeding that of China and establishing India as the most populous country in the world. The growth trajectory remains robust, with India registering a daily number of babies born of 86,000 infants, in comparison to China’s 49,400. In accordance with projections from the United Nations, if India’s population growth continues at a moderate pace, it is anticipated that the population will exceed 1.5 billion by 2030 and surpass 1.7 billion by 2064.

The growth of the population, particularly the increase in the number of participants in the labour force, is among the five fundamental factors that can facilitate the rapid advancement of economic development in an emerging nation. India is currently distinguished as the world’s youngest major country, with 47% of its population comprising individuals below the age of 25 years. This demographic cohort constitutes 20% of the global youth population. It is beyond doubt that India’s youthful population will become the world’s largest consumer base and labour force in the future.

It is evident that India is entering a period of demographic dividend. Professor Mark Fraser, Director of the India-China Institute at The New School in New York, posited that India’s population growth reforms from the 1990s are now entering a dividend phase.

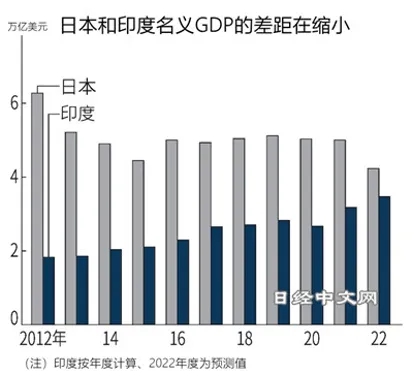

Secondly, GDP growth is fast in India, which gives it possibility to surpass Japan and become the fourth-largest economy in the world by 2027. In 2022, India’s GDP surpassed that of the United Kingdom, establishing it as the fifth-largest economy globally. Currently, the discrepancy between India and Japan, currently ranked fourth, is diminishing. In accordance with projections from the International Monetary Fund (IMF), India’s economy is expected to sustain a growth rate of 6% following 2023. There is a substantial probability that India will surpass Japan and emerge as the fourth-largest global economy by 2027.

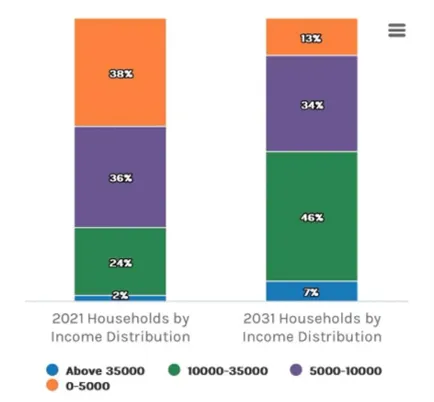

Thirdly, the middle class in India is growing fast, which is leading to an increase in consumer spending. It is anticipated that by 2031, there will be a doubling of household consumption. As forecast by Standard & Poor’s, India’s real per capita income is projected to grow by 5.3%. This will position Indian households as the largest spenders among G20 economies.

Most notable in this trend is the significant increase in the number of middle-class households (with annual incomes between $10,000 and $35,000). Research by Morgan Stanley suggests that by 2031, middle-class and higher-income households in India are projected to account for more than half of all households. At the same time, the number of extremely poor households is expected to fall to a third of its 2021 level.

The shift in social classes signifies a considerable expansion of India’s consumer market. A report by Morgan Stanley indicates that India’s overall consumer market is projected to more than double by 2031. Additionally, the World Bank anticipates that by the centenary of India’s independence in 2047, the country’s consumption levels will reach those observed in middle- to high-income countries.

The potential of the Indian market is evident. However, as we observe the expansion of business opportunities, it is essential to remain mindful of “the three slow” in the Indian market:

The first “slow” is the slow growth of new employment, and the “demographic dividend” is also “demographic pressure”. India experiences an influx of over 20 million individuals in the working age demographic on an annual basis; however, the current employment situation indicates that only 8 million of these individuals are able to secure employment. Even when accounting for the informal economy, the nation is required to generate a minimum of 9 million new jobs annually in order to match population growth. In the absence of adequate employment opportunities, surplus labour may be at risk of either unemployment or a return to traditional agricultural occupations.

In an April article titled “Hype about the ‘Indian Century'”, Princeton University visiting professor and Indian economist Ashoka Modi explicitly asserted that India’s journey towards becoming a global economic powerhouse is fraught with significant challenges and is likely to be prolonged, primarily due to slow job creation and inadequate educational attainment levels among its population. India authorities emphasised that the challenging employment landscape could slow the realisation of India’s demographic dividend down, potentially transforming it into a demographic pressure and giving rise to social unrest.

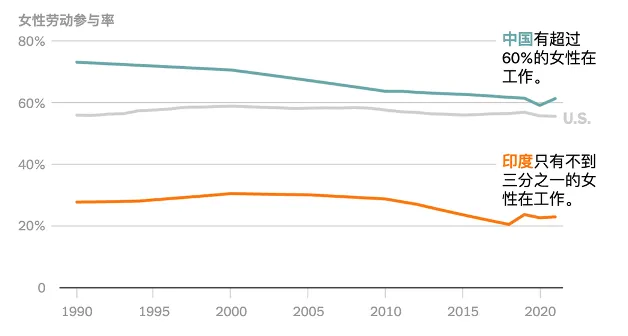

The second “slowdown” pertains to the gradual evolution of social attitudes, particularly evident in the low participation of women in the workforce and the deeply ingrained caste system. Despite the enthusiastic adoption of Western business practices in India, patriarchal values continue to exert a dominant influence on the country’s social and cultural landscape. A striking illustration of this is the fact that less than 20% of women in India work outside the home, which places it among the countries with the lowest rates of female workforce participation globally. In India, traditional norms continue to stigmatise women who work outside the home, often leading to their cessation of employment once their familial financial needs are met.

Moreover, the caste system persists as a deeply entrenched institution in India, engendering insurmountable bounds between disparate castes and exacerbating the pervasiveness of severe social stratification. Notwithstanding constitutional prohibitions against caste discrimination, the lowest caste group, designated as “Dalits”, is frequently confined to menial occupations such as sanitation work, garbage collection, and leatherwork.

In a public statement, the late prominent politician and former Prime Minister of Singapore, Lee Kuan Yew, asserted that India’s caste system and enduring internal ethnic and religious strife present considerable obstacles to meaningful economic advancement. This, he argued, places India at a distinct disadvantage relative to China.

The third “slow” is the slow development of the manufacturing industry as a whole. While there has been an improvement in the atmosphere, it has not been accompanied by a corresponding improvement in substance. Indeed, it was not until 2022 that there was a turnaround. The sector’s inadequate foundation and anemic growth impede the realization of India’s market potential. Strong foundation of the manufacturing industry can bring sufficient jobs, absorb a large number of labor and continue to drive the quality of the labor force to improve, for the economic development of reserves of kinetic energy, these are precisely India’s urgent need.

The Indian government has demonstrated a commendable commitment to the advancement of the manufacturing sector. Prime Minister Modi initiated the “Make in India” initiative during his first term in office and introduced the “Make in India 2047” initiative by the end of 2021. This was done with the objective of making India the world’s third-largest economy by 2047, and of enhancing India’s overall business environment and attractiveness to foreign investment on an ongoing basis.

The Indian government persists in implementing a plethora of alluring industrial policies, encompassing a spectrum of sectors from consumer electronics to semiconductors, accompanied by an array of subsidy programs. These initiatives are specifically designed to attract foreign investment, with the aim of facilitating modernisation and enhancement of India’s manufacturing sector.

In a recent statement, India’s Minister of Industry and Information, Chandrasekhar, articulated a clear and ambitious vision for the country’s role in the global semiconductor ecosystem. He asserted that India aims to establish a robust, dynamic, and competitive presence within the next decade. “We want to accomplish what our northern neighbour have not accomplished in 20 years at a cost of $200 billion!”

Although the outlook appears promising, a closer examination reveals a somewhat sobering reality. From 2011 to 2022, the manufacturing sector’s contribution to India’s GDP has declined by over 5%. In objective terms, this performance is still considerably less impressive than that of Japan in the 1960s-80s and China in the 1980s-90s.

However, in 2022, a favourable turn of events has emerged for this ancient nation on the Indian subcontinent. This is the globally prevalent strategy of “de-risking.”

In 2022, a global phenomenon of “de-risking” emerged within the manufacturing sector. This involved companies diversifying their industrial operations across multiple regions with the objective of mitigating the risks associated with centralising their supply chains. The transfer of major factories as well as foundries became the hottest topic.

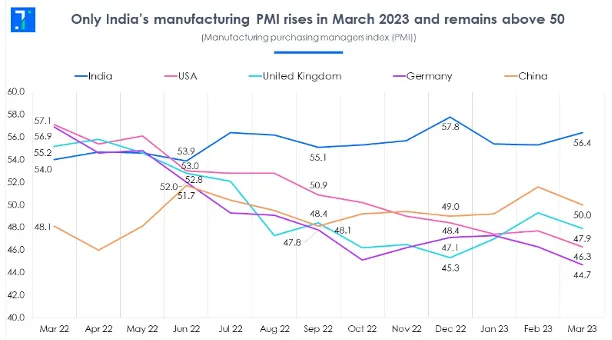

The “de-risking” movement has driven the Indian Industrial Manufacturing Index to consistently remain above 50 throughout 2022. This is indicative of a positive signal, reflecting a period of stable expansion in India’s manufacturing activities over the course of the year. In contrast to the performance of major global economies, which is characterised by signs of decline amid high inflationary pressures, India’s exceptional economic performance is worthy of note.

In response, Zhou Zhanggui, chief advisor at Sinnvoll Consultancy, argues: “While India may not be the primary beneficiary of ‘de-risking’, there is no doubt that without this external impetus, India’s manufacturing sector would not have achieved such a remarkable feat”.

Investment in India: Is it a paradise or a graveyard for foreign investments?

With India’s rapidly developing market, companies from around the world are eager to capitalise on opportunities in India. But can investing in India guarantee profits?

Indeed, it is difficult to ascertain.

The adverse business environment has consistently posed a significant barrier to India’s economic progress.

A review of the history of foreign investment in India reveals a narrative characterised by significant challenges and difficulties. It is inevitable that this narrative is intertwined with the intricate complexities of India’s historical context.

The first foreign investment company to establish a presence in India was the renowned Dutch East India Company.

The foundation of the company was established in 1602, with its arrival in India occurring the following year. At that time, the East India Company employed India as a strategic base from which to establish economic monopolies across Asia, thereby accruing substantial profits through the control of trade routes and commodities. Given that India was a Dutch colony, the East India Company also levied tariffs on goods traded there.

As estimated by the World Bank, the Dutch East India Company reached a valuation of $9 trillion at its zenith, thereby becoming the most valuable company in human history. This valuation is equivalent to the combined gross domestic product of the Netherlands, France, and Germany.

In some ways, India’s historical experience of over four hundred years of colonial rule and exploitation has resulted in a profound distrust of foreign capital among the general public. This extends to investors from the UK, US, China, Japan, and South Korea.

This deeply ingrained pre-colonial nationalist sentiment within Indian society may be temporarily subdued, but it often resurfaces intermittently. Consequently, a peculiar situation arises whereby India attracts investment while simultaneously imposing restrictions on foreign capital.

Since India’s independence in 1947, the country has experienced three distinct phases of foreign investment.

1947–1973 : a system of protectionism and import substitution policies. Following independence, the Indian government categorised industries into four groups and introducing a licensing system. The state exercised tight control over heavy industries and crucial economic sectors such as telecommunications, finance, and insurance, only a portion of the consumer goods industry is open to the private sector. 1970 Indian patent regulations: no product patents for pharmaceuticals, food and chemical products, only process patents to avoid paying high royalties on drugs.

1973-1990 : Liberalize some markets but strengthen regulation. In 1973, India introduced its third industrial policy, which actively promoted foreign and private sector involvement in critical industries. By 1980, India had initiated economic reforms with the objective of increasing its appeal to foreign investment. However, both foreign enterprises and major Indian corporations remained subject to stringent control by the central bank and finance ministry.

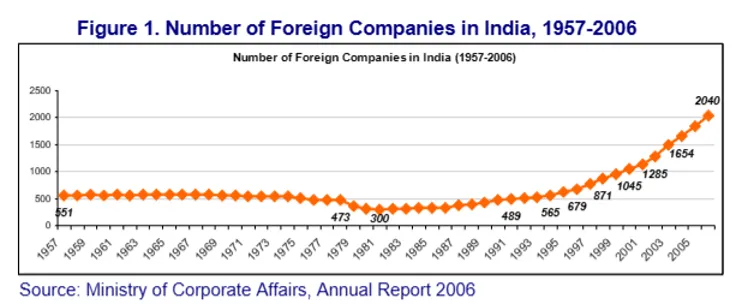

1991-2023: Large-scale investment. In 1991, India dismantled the licence raj, thereby bringing to an end import substitution policies and effecting a transition to export-oriented strategies. This included a substantial reduction in tariffs, with the average tariff decreasing from 150% in the period preceding 1991 to 30%. This resulted in large increase in the number of foreign-funded enterprises in India. In 2004, Prime Minister Singh introduced the “Shining India” slogan during elections, underscoring the government’s commitment to improving the business climate and attracting greater foreign investment opportunities to India. Since Prime Minister Modi assumed office in 2014, a series of initiatives, including “Make in India,” “Digital India,” and “Startup India,” have been launched with the objective of establishing India as a global hub for manufacturing and IT industries.

During this period, a considerable number of foreign companies tried to open up the India market. Some were able to achieve successful expansion, while others encountered difficulties in maintaining their operations, resulting in many of them ultimately withdrawing from the market due to financial losses.

In the retail industry, where the threshold is relatively high, foreign giants have not been able to make a breakthrough. Both Metro and Carrefour have formally withdrawn from the Indian market. Meanwhile, although Walmart Group remains active in the region, it has increasingly shifted its focus towards online operations.

In the automotive manufacturing sector, India, the fourth-largest automotive market in the world, has successfully attracted a multitude of global automotive brands to establish manufacturing plants over the past three decades. However, in 2021, a number of prominent international automotive brands, including American manufacturers Ford and General Motors, French brands Renault and Peugeot Citroën, and German brand Volkswagen, announced their withdrawal from the Indian market, and closed their manufacturing facilities in India. Nissan and Škoda continue to engage in the sale of vehicles in India, although they have indicated that they will not be introducing new models.

It is evident that a considerable number of overseas businesses have ceased operations in the Indian market. Nevertheless, it is also worth noting that there have been a number of notable success stories. In order to illustrate this point, we will present a few typical cases here.

Case One: Coca-Cola

It is noteworthy that in India, while only 10% of villages have access to drinking water, Coca-Cola is accessible in 90% of villages.

Coca-Cola initiated operations in India in 1950. In 1977, in consequence of governmental regulations mandating multinational corporations to transfer equity ownership, Coca-Cola withdrew from the Indian market. However, Coca-Cola resumed its operations in India in 1993 following adjustments to the relevant policy.

To facilitate its integration into the Indian market, Coca-Cola promptly acquired the indigenous carbonated beverage brand Double Seven. This acquisition enabled Coca-Cola to establish a robust brand presence with remarkable swiftness, leveraging Double Seven’s production and distribution networks to reinforce its position in the beverage market, including remote rural areas.

Furthermore, in order to more effectively meet the needs of Indian consumers, Coca-Cola has implemented a series of modifications to its product flavor, with a particular focus on the promotion of Thums Up cola and Maaza mango drink.

In terms of pricing, Coca-Cola has adapted its strategy in India, where income distribution is uneven and social stratification is substantial, to offer products in diverse sizes and packaging formats. This approach guarantees that consumers from diverse socioeconomic backgrounds can obtain products that align with their financial limitations.

In its marketing strategies, Coca-Cola has been an early adopter of integrating elements of Indian culture into its campaigns. The brand collaborated with prominent figures in Bollywood and sports to enhance consumer trust in India.

Currently, Coca-Cola has a dominant market share of over 60% in India, thereby establishing itself as the foremost soft drink brand in the country.

Case Two: Unilever

A notable highlight is that “out of 10 Indian households, 9 use Unilever.”

In terms of time, Unilever was among the earliest foreign companies to enter and establish a presence in the Indian market. Notwithstanding the considerable macroeconomic environment shifts that have occurred in Indian market over time, Unilever has consistently maintained its presence in the market. Conversely, Unilever was firmly committed to long-termism, which has enabled it to become the largest FMCG (Fast-Moving Consumer Goods) company in India today.

Following its listing in India, Unilever has become the fifth-largest company in terms of market capitalisation, with a 16% increase turnover during the 2022 financial year. By 2023, the market capitalisation of Unilever India had reached $23 billion, thereby securing a position in India’s top ten and establishing itself as the second-largest business unit of Unilever worldwide.

The success of Unilever in India can be attributed to the company’s long-term strategy.

The concept of localised operations has been a fundamental tenet of Unilever’s corporate ethos . In 1924, Lever Brothers, a UK-based company, established the inaugural small soap factory in Mumbai. In 1931, the inaugural plant for vegetable fats was established, and in 1943, the first factory for personal care products, including face creams and razors, was constructed in Kolkata.

Following the attainment of independence, India initiated a programme of socialist reforms and implemented import substitution policies, with a particular emphasis on the promotion of domestic production. This policy had negative impacts on the majority of foreign enterprises, yet Unilever was able to circumvent these challenges due to the fact that its factories were situated within India. Notwithstanding the challenges posed by government price controls, which led to a decline in its vegetable oil business from 30% in 1948 to 18% in 1965, Unilever achieved notable success in the detergent sector. By 1967, Unilever’s annual sales in India had reached approximately 10 million rupees, positioning it among the top five private enterprises in the country.

In response to a shifting macroeconomic landscape, Unilever acknowledged the imperative of localization. During the 1950s, it undertook three pivotal measures: firstly, reorganizing its diverse operations in India under Hindustan Unilever Limited; secondly, initiating a public offering by divesting 10% of its shares in 1956; thirdly, appointing Indian scientist Danton as Chairman of Hindustan Unilever Limited in 1961, marking the first instance in history of a foreign company appointing an Indian as Chairman.

During his tenure, the company adopted a more comprehensive localisation strategy. In the field of public relations, it collaborated with the government and other major state-owned enterprises with the objective of strengthening the company’s presence in India. In the domain of social responsibility, he initiated the Eta Dairy project and implemented a series of initiatives with the aim of promoting rural development. In the area of management, there was a sustained effort to cultivate local talent, with indigenous executives having been employed since the 1960s.

The success of Hindustan Unilever Limited (HUL) can be attributed to its comprehensive and ongoing research into the grassroots markets of India.

HUL introduced a model named “Winning In Many Indias,” which categorized India into 15 consumer clusters, thereby facilitating the development of tailored strategies for product development and marketing. The model was supported by 16 business teams whose remit included long-term data collection, SKU management, packaging, labelling and the implementation of ongoing micro-innovations. This comprehensive strategy enabled the brand to align its offerings with consumer preferences and achieve a gradual increase in market share.

By employing a methodical, long-term strategy and comprehensive preparation, Hindustan Unilever was able to achieve a thirtyfold increase in Lifebuoy product sales during the 2020 pandemic. Additionally, the company successfully introduced 17 new hand sanitizers within a span of 100 days.

Moreover, Hindustan Unilever has reinforced local development in India through investments in manufacturing facilities, research and development centres, and foundations, thereby earning enduring trust from Indian society.

The representative of Hindustan Unilever posited, “In India, dialects, customs, and rituals undergo significant changes every 100 kilometers. A homogeneous assumption regarding a country as diverse as India would fail to recognise the significant cultural and business opportunities that exist within its many regions.”

In conclusion, the growth of Hindustan Unilever is not merely fortuitous; rather, it is the result of the company’s strategic market perspective, which is characterised by a consistent focus on long-term cultivation in order to surpass business cycles.

Case Three: Haier China

The standout feature is “Chinese brand, manufactured in India.”

The story of Haier Group in India has largely remained under the radar.

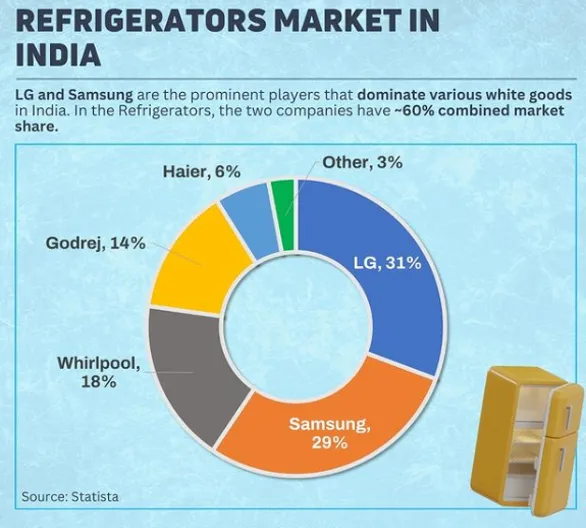

Haier entered the Indian market in 2004, and by 2018, its net sales in India had reached 3,500 million rupees (490 million USD). It is projected to reach 80,000 million rupees (1.1 billion USD) by 2023, with an annual turnover growth rate of up to 33%. Currently, in the Indian home appliances sector, Haier ranks as the third largest brand, following Samsung and LG.

In India, Haier employs a “integrated management” local strategy to establish research and development, along with production bases. Since its initial foray into the Indian market in 2006, Haier has made significant investments in the country, culminating in the establishment of a 36,000-square-metre manufacturing facility in Pune, India.

The facility was originally established as a refrigerator factory but has since evolved into a comprehensive industrial park. It now produces a range of appliances, including refrigerators, washing machines, air conditioners, LED TVs, and water heaters. The facility has an annual production capacity of 1.8 million refrigerators and 500,000 units each of washing machines, air conditioners, LED TVs, and water heaters.

In March 2019, Haier constructed a second manufacturing facility in the northern region of India, situated in Noida. It is anticipated that this expansion will result in a more than doubling of production capacity. At present, over 95% of Haier products sold in the Indian market are manufactured locally. This strategy serves to reinforce the company’s proximity to the local market, while simultaneously insulating it from potential geopolitical factors.

In terms of product development, Haier has conducted a comprehensive analysis of consumer usage patterns and regional preferences in India. In response to the observed preference among Indian consumers for refrigeration over freezing functions, Haier introduced the BM series of refrigerators in 2016. The models in question feature the refrigerator section on top and the freezer section below, thereby reducing the likelihood of users bending over to pick up something by 90 percent. Moreover, Haier introduced a washing machine with an absence of partitions and the Dawn series of smart inverter air conditioners. Both innovations have received consistent praise from the market.

Similarly to Coca-Cola, Haier plays a significant role within India’s distribution network. The company operates 2,000 company-owned stores and 15,000 dealer stores throughout India, thereby ensuring extensive coverage across cities and towns of varying sizes nationwide.

Case Four: Amazon

The standout feature is its transformation “from humble beginnings to an industry giant.”

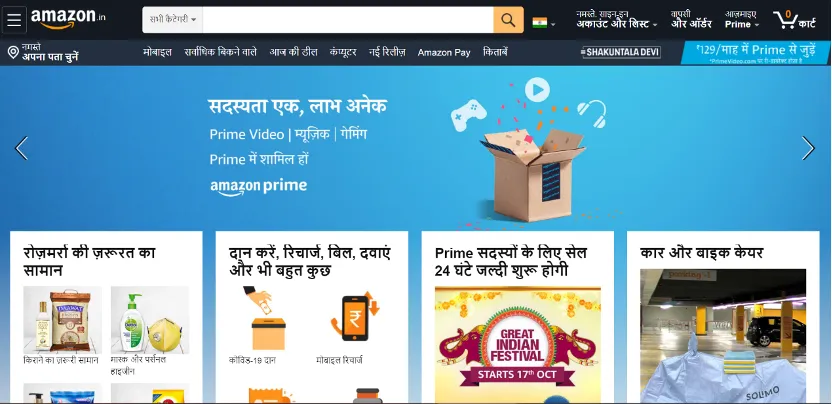

In contrast to manufacturing sectors such as consumer electronics and home appliances, the retail and e-commerce industries in which Amazon operates in India have been subject to stringent regulations. The Indian government has imposed stringent limitations on online sales by foreign brand retailers. In essence, Amazon was initially permitted to operate solely as a third-party distributor, exclusively selling Indian products.

In 2013, Amazon initiated the launch of its Amazon India website, and commenced a significant undertaking aimed at the recruitment of retailers. In order to achieve this objective, Amazon implemented the “Amazon Chai Cart” programme. This initiative involved the deployment of mobile carts bearing the Amazon brand throughout India. These carts provided tea to small business owners while simultaneously educating them on the processes of listing and selling their products on the Amazon website. The Chai Cart initiative saw Amazon cover 31,000 kilometres across 15 cities, engaging with over 10,000 sellers.

In 2016, Amazon introduced the “Amazon Tatkal” programme, which involved the conversion of microbus into mobile studios, providing interested sellers with immediate access to a range of services, including registration, imaging, and cataloguing. This enabled them to register with Amazon and commence real-time sales of their products rapidly.

Following the recruitment of vendors, Amazon proceeded to extend its operations with the introduction of a centralised logistics platform, specifically designed for the Indian market and known as Fulfillment by Amazon. Merchandise is dispatched by sellers to one of Amazon’s 21 warehouses situated in India, where Amazon oversees the integrated processes of packaging and shipping.

In 2014 and 2015, Amazon introduced two new programs, Easy Ship and Seller Flex, which were focus on the Indian market. Easy Ship enabled Amazon to pick up the goods directly from the sellers’ locations and integrate them into the Amazon logistics network. Seller Flex involved Amazon providing training to sellers with the aim of improving their warehouse operations, while Amazon assumed responsibility for the final delivery logistics.

In order to enhance its shipping services, Amazon entered into agreements with India Post and various airlines, and established a sizeable fleet of bicycles and motorcycles for the final stage of delivery.

Amazon’s research and development investments tailored to the Indian market are worthy of particular note. In light of the relatively slow internet speeds that are a feature of the Indian context, the operation of the original website on mobile devices is difficult. Consequently, Amazon has developed a mobile application that is both memory-efficient and operates without issues even on 2G networks.

Additionally, the Amazon India website faces a number of challenges, including the presence of counterfeit products, fraudulent reviews, and deceptive transactions. In response to these issues, Amazon has established a significant research and development centre in Bangalore. The facility is dedicated to the meticulous comparison of products and reviews, with the objective of enhancing the service environment.

Furthermore, fixing the position in India presents a considerable challenge. Amazon has employed artificial intelligence (AI) and machine learning from the outset to assign delivery scores to addresses, thereby enhancing the precision of its delivery operations.

In terms of pricing, Amazon India utilises a model that is distinct from that observed in the US market. In India, the annual fee for Prime membership is 999 rupees (equivalent to approximately 14 USD), which is significantly lower than the 119 USD charged in the US. Similarly, the cost of an Amazon Audible membership is 199 rupees (equivalent to 3 USD), while a Kindle membership is priced at 169 rupees (equivalent to 2.7 USD). Subscribers are able to access a diverse range of music, films and literature in Hindi and other Indian languages.

At the time, Amazon is the most prominent online retail brand in India. The erstwhile dominant player, Flipkart, has been acquired by Walmart, while Snapdeal is basically ousted.

In addition to the unceasing endeavours of these overseas enterprises operating within India, the Indian government has initiated significant reforms with the objective of optimising the business environment.

In order to facilitate the incorporation of companies in a more efficient manner, India has introduced the SPICe+, a online registration system. In 2020, India unveiled a series of comprehensive administrative reforms with the objective of streamlining administrative procedures through online approvals, reducing bureaucratic steps, and improving transparency and efficiency.

India has engaged in significant infrastructure development across a range of sectors. In the field of highway development, the government has initiated two major programmes: the National Highway Development Programme and the Bharatmala Pariyojana. The implementation of railway reforms has resulted in the introduction of independent operators, including the Tejas Express and the Vande Bharat Express, which have enhanced both the speed and comfort of rail transport. The Sagarmala Programme, initiated by the Indian government, is a port modernisation and regional development initiative centred around ports. Furthermore, there is a drive to foster public-private partnerships and leasing arrangements with the objective of engaging private enterprises in the comprehensive development and operation of ports.

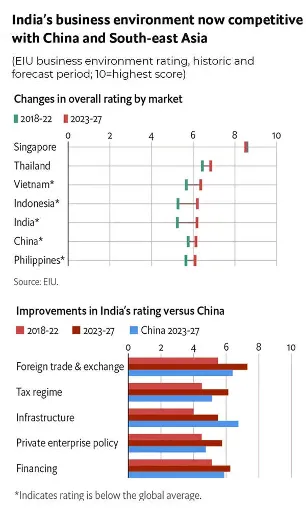

In recent years, India has made notable progress in enhancing its business environment. As evidenced by research from the Economist Intelligence Unit (EIU), India’s global business environment ranking has exhibited a notable improvement, rising from 62nd place in 2018 to 53rd place. Within the Southeast Asia region, India’s ranking also increased from 14th place in 2018 to 10th place by 2022, placing it on a par with Indonesia. In the period between 2023 and 2027, India is expected to continue implementing reforms, as indicated by data from the Economist Intelligence Unit (EIU). These reforms will focus on enhancing efficiency in foreign trade and investment, implementing tax reforms, supporting private enterprises, and strengthening financial operations.

The “One Country, One Strategy” global localisation research team at Sinnvoll Consultancy posits that foreign companies with robust localisation capabilities in India have the potential to achieve significant success in the country.

03

Chinese Companies: Do they still have opportunities in India?

In light of the aforementioned analysis, it is evident that the Indian market can offer Chinese enterprises a range of opportunities and challenges.

Based on our research on the business development of more than 30 foreign companies in India, we would like to offer our insights and recommendations for Chinese companies wishing to work in the Indian market on a long-term basis:

Firstly, it is imperative that production is localised in order to ensure success in the Indian market. It is irrefutable that, whether in the consumer electronics, semiconductor, automotive, or consumer goods sectors, localising production is an indispensable prerequisite for the continued success of operations in India.

Therefore, India employs a carrot-and-stick approach—raising tariffs on one hand and increasing subsidies on the other. However, policy alignment is just one facet. More crucially, establishing a robust brand presence in Indian society and cultivating closer connections with Indian consumers are imperative. As previously mentioned, Indian society retains significant skepticism towards foreign investment. This sentiment is akin to a ticking time bomb; once ignited in the public sphere, Chinese enterprises may encounter widespread criticism, leaving them in a precarious position—either stagnate or exit the market entirely.

Secondly, when pursuing market development in India, it is of paramount importance to adopt a dynamic and long-term perspective.

The findings of Sinnvoll Consultancy’s research indicate that instances of tax harassment and extortion by local officials in India are pervasive. In the previous year, Samsung was subjected to allegations of tax evasion, while this year, both Xiaomi and Amway have confronted analogous challenges, resulting in asset freezes.

Consequently, a considerable number of enterprises ultimately decide to withdraw from India, citing the country’s cultural and institutional deficiencies as being incompatible with the requirements of modern multinational corporations.

We maintain a skeptical stance regarding these conclusions.

It is evident that the business environment in India is characterised by a multitude of intricate and dynamic factors. These include administrative procedures, pervasive bribery within local cultures and traditional ideologies that diverge significantly from business norms. Collectively, these elements are hard to adapt for foreign enterprises operating within the country. Instances include foreign companies facing boycotts for promoting employees from lower castes and factories being forced out by local communities for hiring excessive numbers of female workers. The Indian market is replete with uncertainties that present a significant challenge for foreign enterprises, resulting in unpredictable consequences when they become enmeshed in such circumstances.

Nevertheless, historical evidence indicates that economic growth in any country is often preceded by a dark hour. This is exemplified by the experiences of 18th-century Europe, 19th-century United States, and 20th-century East Asia. It is rare for a society to be initially perfectly conducive to business development, particularly for foreign enterprises. It is thus evident that these issues require gradual resolution over the course of development.

The opening up of the Indian economy, particularly in light of the growing influx of international foreign investment, will undoubtedly result in significant changes to India’s business environment.

Foreign enterprises, particularly those operating within the manufacturing sector, will contribute a significant influx of capital, technology, human capital, and advanced management practices to India. This will directly propel the comprehensive upgrade and transformation of the national business infrastructure, thereby providing the impetus for commercial reform in India. Concurrently, the organic growth of commercial civilisation will enhance India’s appreciation of business discipline, prompting multi-tiered policy reforms and facilitating deeper integration into the global economy.

This process is likely to be a lengthy one, with an estimated timeframe of ten to twenty years. Nevertheless, it constitutes a journey that India must undertake.

As Arvind Panagariya, former Chairman of the India Development Foundation, has observed, if India is to sustain economic growth at an annual rate of 8%, it must implement labour reforms, privatisation reforms and measures to mitigate various forms of harassment towards foreign investment. In order to remain competitive on the global stage, it is imperative that these reforms are implemented across all states. Without them, it is unlikely that foreign capital will be willing to invest.

It could be argued that a static perspective is insufficient for a comprehensive assessment of the current state of the Indian market. A more prudent approach would be to evaluate its future development in a dynamic manner, taking into account the potential for it to progress towards greater openness and integration, or to continue with gradual isolation.

Thirdly, in order to respect the Indian market, it is necessary to align closely with consumer needs in order to develop products that are specific to the Indian market. Despite its geographical proximity to China, India exhibits notable differences in terms of language, culture, and traditions. It is difficult for Chinese companies going overseas to directly replicate their Chinese model or Southeast Asian experience to the Indian market. Consequently, the Indian market requires the development of products and services that are specifically adapted to its distinctive preferences.

An analysis of the successful experiences of foreign enterprises in India reveals that companies such as Coca-Cola, McDonald’s, Procter & Gamble, and Unilever in the consumer goods sector, along with Samsung, LG, Haier, Xiaomi, and Vivo in the consumer electronics industry, and even e-commerce giant Amazon, are all formulating business strategies, product designs, and operational processes that are tailored to the Indian market. In essence, every aspect of these companies reflects respect for the local market and extreme thinking about user needs.

Fourthly, At a lot of times, Chinese companies need to take a step back and curve forward. In contrast to the business environments of developed markets in Europe and America, although the business environment in India has been optimized in recent years, it is still changing too fast for Chinese companies. Two principal factors contribute to this challenge. Firstly, India’s policy stance towards China has become increasingly stringent. In 2020, the Indian government introduced Press Note 3, which concerns direct investments from China. This note mandates Chinese investors to report and obtain governmental approval for investments in critical sectors. This is indicative of India’s cautious approach towards Chinese businesses. Secondly, there is an increasing level of scrutiny and multiple investigations targeting Chinese enterprises, which may result in penalties such as fines or asset freezes for any violations.

Although it is said that in the history of foreign investment, there are also companies like Vodafone which can mediate with the Indian Government for more than a decade and eventually resolve their disputes with the Indian Government through the International Court of Arbitration.

Nevertheless, in light of the currently unstable bilateral relations between China and India, the probability of the imminent signing of investment and trade protection agreements is minimal. In the absence of a transparent contractual framework for trade collaboration with India, Chinese enterprises will be compelled to demonstrate enhanced flexibility and strategic foresight to ensure the success of their developmental initiatives in India.

The ancient land of India has nurtured ancient civilizations full of spirituality and wisdom and has also been ravaged in the course of modern history. In the present era, India evinces the image of Vishnu, emerging from a protracted period of repose, with the intention of reclaiming its erstwhile potency, majesty, and resplendence.

India is progressing rapidly。 This progress is accompanied by the movement of torrents and sediments alike. India’s progress is shaped by intricate societal complexities, which undoubtedly impede business efficiency. However, these complexities are also molded and influenced by the evolution of commercial civilisation.

As Sinnvoll Consultancy’s “one country, one policy” global localisation concept indicates, the path of Chinese enterprises in India will undoubtedly be fraught with risks and challenges. However, for those who possess the requisite courage and vision, the immaturity and uncertainty of the Indian market represent merely one aspect of a coin. The other aspect is the existence of significant business opportunities and potential. We have reason to expect that, in the near future, India will become a stage for certain Chinese companies to develop and grow.

It could be argued that the Indian market is akin to an “adventurer’s paradise”, with a hint of Shanghai Tang’s distinctive style. Despite the inherent risks, for China’s globalized companies, “missing out on India” is likely to be a historically significant miscalculation.

Reference:

- General History of India, The Commercial Press

- A history of modern India, 1480–1950, Markovits Claude, 2004, Anthem Press

- How Ideology Shapes Indian Politics, Nicholas Haas, Rajeshwari Majumdar, 18/12/2023, CSIS

- India Overview: Development News, Research, Data, 29/09/2023, The World Bank

- Chinese handset companies low share in India’s exports draws govt ire, Kiran Rathee, 30/11/2023, The Ecoomic Times

- Despite headwinds, Chinese smartphones continue to dominate India market, Ayushi Kar, 12/05/2024, The Hindu Business Line

- Exclusive: Xiaomi says India’s scrutiny of Chinese firms unnerves suppliers, Aditya Kalra, Munsif Vengattil, 12/02/2024, Reuters

- India no longer a golden goose for China-based smartphone brands, Jingyue Hsia, 13/10/2023, Digitimes Asia

- India wants to become the top manufacturing alternative to China. But first it needs to beat Vietnam, Charmaine Jacob, 01/04/2024, CNBC

- L’Inde rêve de remplacer la Chine comme usine du monde, Carole Dieterich, 22/02/2024, Le Monde

- Chinese companies to outsource manufacturing to local players, 20/04/2024, India Times