Japan’s mysterious economy has enjoyed a vigorous recovery, with the Nikkei index reaching its highest level in 34 years. Is Japan’s economic resurgence a sign of a turnaround in relation to China? Was the pandemic a coincidence in Japan’s emergence from deflation? Japan is now the focus of increasing attention.

On 22 January 2024, the Nikkei 225 index closed above 36,500 points, its highest level since 1989. In that year, the yen appreciated significantly against the dollar, with the exchange rate improving from 1:250 to 1:120, four years after Japan signed the Plaza Accord. Japan’s economy seemed to be flourishing during this period. Looking back on that year, it was clear that history was approaching a pivotal moment: Japan was undergoing the transition from the passing of Emperor Showa to the enthronement of Emperor Heisei, which coincided with the global event of the fall of the Berlin Wall, marking the end of the East-West division of the Cold War era. In the same year, Japan’s GDP per capita reached $24,822. China’s was just $310, less than 1/80th of Japan’s. But it was also the year when cracks began to appear in Japan’s prosperity, marking the beginning of a period of disillusionment.

The story became increasingly familiar to the Japanese public. After the excitement of 1989, Japan’s economy quickly went into a steep decline. By the summer of 1992, stock prices had fallen by 60% by August 1992, while land values had fallen by 70% since 1990. Between 1991 and 2003, Japan’s GDP growth rate stagnated at just 1.14%, well below that of other developed countries. This period marked Japan’s official entry into the “lost decade”.

Meanwhile, across the Sea of Japan, China’s economic miracle was unfolding. Since 2000, following China’s accession to the WTO, its economy has soared, with nominal GDP growing by 1160%. In stark contrast, Japan’s nominal GDP grew by only 20% over the same period, well below the 160% growth in the United States and 90% in Germany. Not only was this disparity insufficient, it also highlighted Japan’s stagnation. Some have even called it “the Lost Thirty Years of the Japanese Economy (1991-2021)” due to the prolonged economic stagnation. This historical comparison objectively illustrates how China’s economic rise coincided with Japan’s declining.

As several key economic indicators show, the Japanese economy has undergone a profound transformation since 2022:

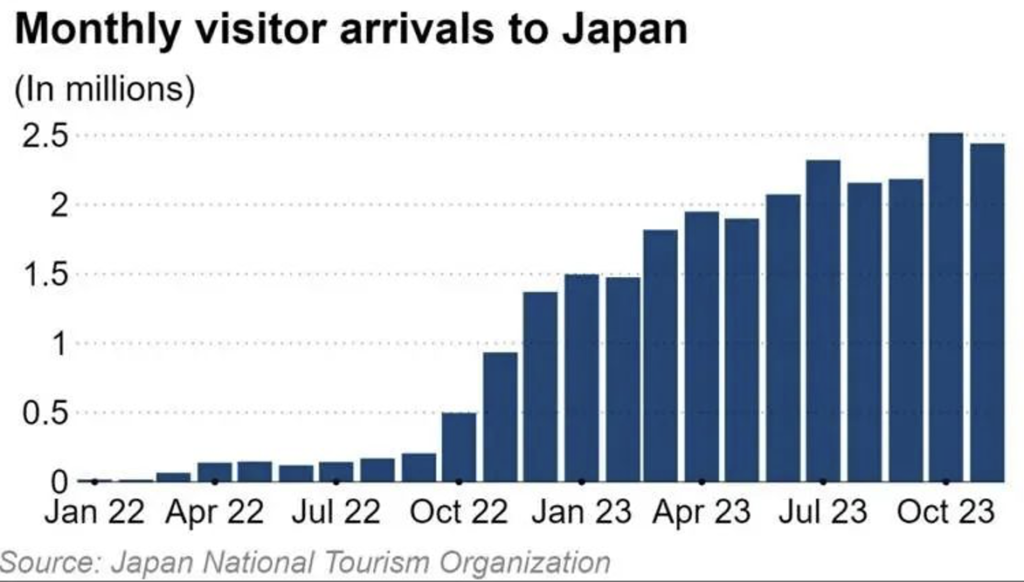

One notable change is the rapid shift in Japan’s gross domestic product (GDP). In the first half of 2023, Japan’s GDP experienced robust growth, which at one point reached as high as 6% on a year-on-year basis. The tourism industry, a key driver of economic expansion, also experienced explosive growth. In 2023, Japan witnessed a surge in global tourism, with 22 million arrivals from January to November, marking a historic high in inbound tourist spending. This influx generated 4 trillion yen (approximately $36.4 billion), a remarkable 4.3 times more than in 2022.

Further analysis of the manufacturing diffusion index shows optimism among Japanese companies. In the fourth quarter of 2023, the main diffusion index for large manufacturers rose from 9 to 12, while large non-manufacturers increased from 27 to 30. The manufacturing index for the automotive sector rose from 15 to 28, and the confidence among electrical machinery manufacturers improved from -2 to +4. Large hotels also recorded a significant increase in confidence, rising from 44 to 51.

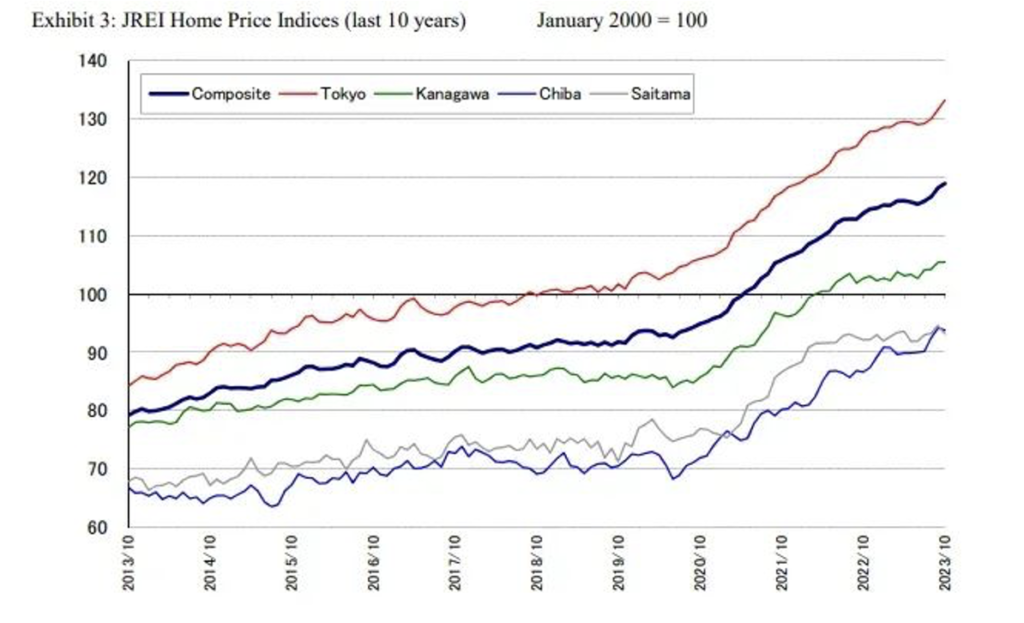

Japan has seen remarkable developments in the real estate sector, with a surge in investment across the property market. In the first half of 2023, Tokyo’s average new apartment price jumped 60% to a record high of 130 million yen (about $856,000). The Tokyo, Osaka and Nagoya metropolitan areas all saw urban land prices rise by over 1% in 2023. Other metropolitan areas also grew for the first time in 31 years.

This time, Japan’s economic recovery is taking place in the midst of China’s robust manufacturing advantage and with little change in Japanese household incomes. This situation raises new questions and challenges: Is Japan truly experiencing an economic revival after three decades of stagnation? What are the underlying reasons for this revival? Is this economic recovery the result of gradual accumulation or a temporary phenomenon?

Song Xin, founder of Sinnvoll Consultancy, and a number of researchers jointly launched a comprehensive study of the Japanese economy and market, and conducted field research and business interviews in Japan for nearly a month, aiming to provide policymakers with more powerful decision-making support through in-depth analysis, and presenting readers with reflections and findings in three different dimensions in this article: Review: The Emergence and Demise of the Japanese Economic Miracle after World War II, Reform: Economic recovery in the Koizumi and Abe eras, Outlook: Japan’s economy enters a new era.

Review: The Emergence and Demise of the Japanese Economic Miracle after World War II

In order to gain insight into the underlying causes of the recent resurgence of the Japanese economy, it is crucial to comprehend the factors that led to its decline during the previous economic cycle. This article will present a brief overview of Japan’s economic trajectory since the Second World War.

The celebrated American economist and Nobel laureate in economics, Milton Friedman, is reputed to have observed that “The best way to grow rapidly is to have the country bombarded”. Indeed, the post-war reconstruction period marked the beginning of Japan’s economic miracle.

On 14 August 1945, Japan surrendered unconditionally at the conclusion of the Second World War. During the war, Japan inflicted immeasurable damage on the global community and on its own population. In the aftermath of the war, Japan experienced a significant decline, with per capita GDP returning to a level comparable to that of the Meiji Restoration period. However, this level was only one-tenth of that of the United States in the same period of time.

On this basis, Japan proceeded to embark on a phase of accelerated development.

During the economic recovery period 1945-1956, we saw Japan embark on a significant programme of post-war reconstruction. During this period, Japan’s real per capita GDP exhibited a rapid growth trajectory, reaching levels comparable to those observed in the 1940s by 1956. The compound annual growth rate of per capita GDP was 7.1% over the course of this period.

Subsequently, Japan entered a period of accelerated growth that persisted until 1973. By the conclusion of this phase, the country’s per capita GDP had reached 95% of that of the United Kingdom and 69% of that of the United States, underscoring the remarkable pace of its economic development.

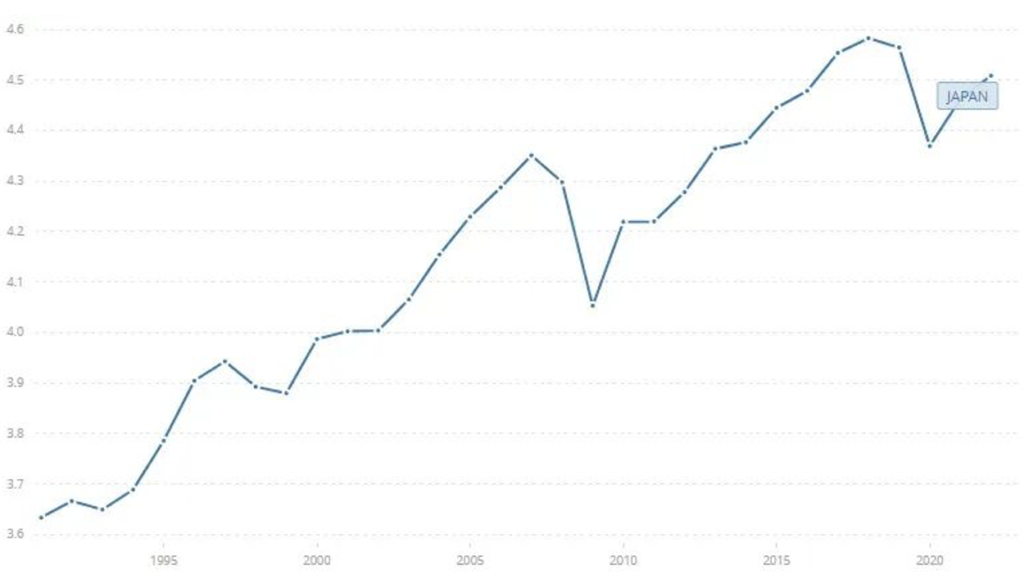

By 1991, the final year of the “bubble economy,” Japan’s per capita GDP had reached a level exceeding that of the United Kingdom, attaining 120% of the UK’s level and 85% of the United States’. At this juncture, it can be posited that Japan had essentially caught up with Western economies.

In order to elucidate the underlying rationale that facilitated Japan’s remarkable economic growth in the post-World War II era, Song Xin, the founder of Sinnvoll Consultancy, posits four key points.

Firstly, Japan introduces technology to rapidly change production methods. In the aftermath of World War II, Japan suffered a significant decline in its industrial capacity, with more than a quarter of its industrial output lost. This resulted in a considerable portion of the remaining capital stock becoming obsolete. Both the Japanese government and entrepreneurs were aware that innovation was essential for rebuilding from the ground up. Consequently, Japan initiated an extensive programme of technology importation from abroad since the post-war period. The chart below illustrates the volume of technology import contracts Japan entered into during the 25 years following the Second World War, with a particular focus on sectors with substantial growth potential, including iron ore, steel, petrochemicals, electronics, and automotive manufacturing.

To bolster the technological transformation, the Japanese government implemented several supportive policies. On the one hand, an expansionary monetary policy was pursued with the objective of ensuring the availability of inexpensive funds to support technology imports. On the other hand, the government exercised close supervision over loan conditions with the objective of preventing excessive lending and borrowing, thereby maintaining a low-interest rate environment.

During that period, Japan’s approach to the importation of foreign technology and products could be characterised as “enthusiastic”, bearing resemblance to China’s strategy of attracting foreign investment in the aftermath of the country’s reform and opening-up policy. To illustrate, in 1963 the Japan Science and Technology Information Center (JICST) roduced 210,000 abstracts of foreign scientific papers with the objective of providing symmetrical access to information on cutting-edge developments both domestically and internationally. Moreover, in order to facilitate the expansion of nascent industries, Japan imported a considerable volume of machine tools and robots for the automotive sector, in addition to generators for public electric utility. Furthermore, Japan did not merely import technologies; it also engaged in the refinement and enhancement of imported technologies. Statistical data from the 1960s indicates that approximately ten thousand large enterprises allocated approximately one-third of their research and development expenditures to the improvement and refinement of imported technologies. This resulted in an average efficiency improvement of over 20% in technological performance.

As economist Alexander Gerschenkron observed, the importation of technologies by Japan encompassed not only material aspects but also societal, economic systems, and institutional dimensions. In the aftermath of World War II, Japan sought to rapidly narrow the gaps in its industrial and economic performance by absorbing a plethora of developmental insights from Western nations. Japan pursued an “economy-first, society-later” development strategy, meticulously crafting and adapting its institutions to focus on achieving breakthroughs. To illustrate, while Western European countries allocated capital towards real estate and social welfare systems, Japan primarily directed its capital into industry, particularly the rapidly expanding manufacturing sector. To ensure the continued efficiency of production, Japan also maintained a long-term low-pay policy for its employees.

Secondly, Japan’s policies facilitated export growth. Taking advantage of overseas technology, Japan experienced a surge in exports in the post-war period, catalysing rapid economic development. The government introduced tax exemptions and offered preferential loans for expenses related to overseas sales, effectively lowering the prices of exported goods and increasing their competitiveness relative to those of other nations.

In order to gain a competitive advantage in the global market and to compete with Western companies, the Japanese government implemented three strategic initiatives.

The first strategy, designated as “administrative guidance,” directed companies towards promising industries through the implementation of a combination of incentives and penalties. This approach was primarily directed towards sectors with international market potential, notably between 1950 and 1965. At the outset, the “administrative guidance” initiative prompted companies to pursue opportunities in the textiles and miscellaneous industries. This was subsequently complemented by a shift towards the machinery sector and later, metallurgy.

The second strategy is “cartels”. To establish a foothold in the international arena, Japanese companies pursued a way of “ initially achieving a dominant market position, and then consolidating their strength”. The Japanese Ministry of Economy, Trade and Industry (METI) frequently turned a blind eye to cartel activities that contravened competition principles, particularly those involving collusion between government and business in the export sector. As a result, over 1,500 cartel cases remained unpunished.

The third strategy pertains to the implementation of exchange rate and trade barrier policies. In the pursuit of enhancing export performance, the Japanese government has consistently maintained a relatively low exchange rate, thereby reinforcing the overall competitiveness of Japanese products. These three strategies were highly pragmatic and effective, playing a pivotal role in advancing Japan’s export growth.

Thirdly, Japan guarantees the quantity and quality of low-priced labour. Behind the exports there is a need for a large labour force to support them. Statistics from the National Bureau of Economic Research in the United States indicate that 30% of Japan’s post-war economic growth was attributable to cost-effective labour. In the period following the war, a significant number of individuals returned to the workforce. However, wage growth remained relatively slow, failing to keep pace with the increases in labour productivity. Consequently, Japanese companies were able to maintain efficient operations and development until the 1980s.

Fourthly, Japan encouraged the expansion of keiretsu. With the support of the Japanese government, large business groups were created. These keiretsu include industrial firms, banks and trading companies that are linked through mutual shareholdings, fostering enduring exclusive relationships and forming deeply integrated business conglomerates.

For example, keiretsu such as the Mitsubishi Group, Mitsui Group, Matsushita Group, Toyota Group and Sumitomo Group were established during this period. These keirestsu boasted substantial financial resources and extensive network connections, making them the pride of their time.

In order to advance the position of leading entities, the Japanese government implemented a series of policies designed to encourage growth. These included tax cuts for large corporations, depreciation incentives and facilitated long-term access to cheap credit. The objective of these corporate groups was not merely to accumulate profits in the short term, but also to expand their market position over the longer term. Consequently, they frequently invested in high-growth sectors with enduring potential, thereby positioning themselves competitively against global industry leaders.

The growth of keiretsu has resulted in two principal consequences. Firstly, it has fostered an intensely competitive business culture, whereby conglomerates are driven to continually update product designs and adopt new production technologies in order to maintain pace with their rivals. This has given rise to intense competition among groups, driven by continuous imitations and improves. In light of the considerable stakes involved, decision-makers are expected to perform flawlessly. In such an environment, employees are expected to work overtime forr long term and demonstrate unwavering loyalty to their organisations. The hierarchical structure within group companies is characterised by a high degree of rigour, commencing with the training phase during which employees are required to assimilate a comprehensive range of company protocols, Including the extent of bowing varies when facing different leaders. Keiretsu frequently utilise rigorous selection processes, comprising multiple rounds of interviews, in order to recruit young talent who are aligned with the competitive culture.

A further notable consequence is the accelerated uptake of novel concepts and technologies across the economic landscape, effectively eliminating promotional barriers between disparate entities. To illustrate, nascent technologies such as preliminary robotics and computer chip fuzzy logic software were integrated into products in an uninterrupted manner. In the context of intense competition among corporate groups during this period, a number of notable industrial practices and methodologies emerged, including Total Quality Control, lean manufacturing, and cross-functional product teams.

Nevertheless, every phenomenon is characterised by a dialectical aspect. The collapse of Japan’s economic bubble in the 1980s was attributed to the negative repercussions of its successful elements. The preceding developmental strategies proved inadequate in adapting to changes in the external environment, resulting in a comprehensive upheaval.

From a macroeconomic standpoint, the international environment that had previously facilitated Japan’s economic growth began to shift in the 1980s. With the conclusion of the Cold War, the earlier East-West ideological divide dissipated, giving way to the emergence of trade deficit among Western countries themselves. Japan, which had previously been a global manufacturing hub, became a focal point for Western nations in terms of trade deficits. This prompted the United States, Germany, France and the United Kingdom to negotiate and sign the Plaza Accord, which resulted in the depreciation of the US dollar relative to the Japanese yen. Japan’s previously robust economic model began to encounter difficulties as a result of a decline in exports.

Subsequently, the Japanese government acknowledged the necessity of implementing structural reforms in order to achieve economic transformation. The 1986 Maekawa Report underscored the necessity for structural reforms and a transition towards a more domestically-driven economic model. However, these reforms were implemented with considerable delay and proceeded at a relatively slow pace, as follow-up developments surpassed the expectations of the policymakers responsible for implementing them.

As the core conflict shifted, what was once envy and admiration for Japan’s corporate development and management system within the Western world was gradually transformed into criticism of Japan’s economic system. For example, during the economic boom in Japan in the 1970s, American society saw a wave of books lauding Japan, including Richard Tanner Pascale’s The Art of Japanese Management. The book in question lauded Japan’s Bottom-up decision-making, its adherence to the Deming-style quality control methodology, and the government’s long-term technological development planning, portraying Japan as a more sophisticated form of capitalism.

However, by the mid-1980s, a growing number of commentators in the American public sphere were attributing Japan’s success to its adversarial trade policies and powerful industrial cartels, which they argued fostered unfair trade practices. Notable works such as The Enigma of Japanese Power: People and Politics in a Stateless Nation and Japan as Number One: Lessons for America, the authors argued that Japan’s achievements were rooted in oligarchic politics that prioritised meeting harsh economic demands over citizen welfare. These commentators proposed that Japanese companies didn’t fare any better; rather, they argued that their success was contingent upon the existence of external conditions that were inherently favourable to them.

From within Japan, in the 1980s, Japan witnessed a surge in real estate and stock market prices, which prompted a surge in borrowing and investment. This ultimately resulted in an unsustainable bubble. Concurrently, from a demographic point of view, Japan’s population had been ageing since the 1970s, the labour market was insufficient to support export industries. This demographic shift prompted many labour-intensive industries to relocate overseas, thereby reducing the tangible support for Japanese assets and contributing to the subsequent economic downturn.

Consequently, a convergence of both internal and external factors began to hit the Japanese economy. A review of Japan’s economic history reveals that, prior to the signing of the Plaza Accord, the country had already exhibited indications of subdued growth. The principal factor responsible for this was the lack of sufficient capacity for autonomous innovation, which is essential for driving economic growth in new phases. Despite the Japanese government’s implementation of loose monetary policies to stimulate investment demand, the economy appeared to flourish on the surface. Nevertheless, in reality, the chances for significant economic investment diminished over time, leading to a persistent decline in investment returns.

The ultimate catalyst was the repercussion of interest rate hikes. In May 1989, the Bank of Japan commenced a series of interest rate increases, implementing five consecutive hikes. Subsequently, in March 1990, the Bank of Japan implemented rigorous restrictions on real estate financing. Notwithstanding these measures, both the stock and real estate markets experienced a significant decline. The reduction of the benchmark interest rate from 6% to 0% proved ineffective in reversing the persistent decline in stock indices. It was not until 2023 that the Japanese stock market reached again a level equal to its peak in 1990.

It is beyond doubt that the collapse of Japan’s economic bubble was an inevitable consequence of the transition that was occurring at the time. This is an example of the adage “success or failure depends solely on one individual” being borne out by events. The factors that facilitated Japan’s accelerated development became significant liabilities in the subsequent era. These underlying reasons were both internal and external, and it would be erroneous to oversimplify them or attribute them to conspiracy theories. It is of the utmost importance that Chinese policymakers consider and reflect upon this perspective.

Reform: Economic recovery in the Koizumi and Abe eras.

The recovery of Japan from its economic nadir was characterised by a series of significant challenges and complexities. This review will examine the political and economic developments of Japan over the past two decades, as well as the strategic thinking of its national leadership.

A cursory examination of Japan’s domestic political landscape since the Second World War reveals a striking phenomenon: the frequent turnover of Japanese prime ministers, which often results in abbreviated tenures that prevent them from leaving a lasting impression. Consequently, few prime ministers since the 1990s have been well-known. It is noteworthy that Junichiro Koizumi (1,980 days) and Shinzo Abe (3,188 days) merit particular mention, with Abe holding the distinction of being the longest-serving prime minister in Japanese history. In this context, only Abe and Koizumi had the opportunity to implement significant changes to Japan’s economic trajectory, and in fact, both were able to reverse Japan’s economic woes.

The actions of two politicians are now to be examined. The first is Junichiro Koizumi (2001-2006). Despite controversial incidents, including visits to the Yasukuni Shrine and support for the Bush administration’s invasion of Iraq, which had a negative impact on his political career, his economic opinions and reforms revitalised Japan’s stagnant economy.

Upon assuming office as Prime Minister in 2001, Junichiro Koizumi initiated a series of reforms, which were guided by three core principles. The three core principles that guided the reforms were as follows: “No reform, no growth,” “Empower the private sector to its fullest potential,” and “Enable local governments to deal with what they can deal with.” These reforms were driven by the conviction that Japan’s economic decline was attributable to an absence of effective structural adjustments, necessitating organisational and procedural reforms to enhance the efficiency of resource allocation. These reforms, which are commonly known as supply-side reforms, had the goal of stimulating economic growth. In addition, the Koizumi administration advocated for a “small government, large market” approach and emphasised decentralisation with a focus on local empowerment. The measures taken aimed to reduce the size of the government, limit intervention, and reduce public spending, thereby enhancing more efficiency optimisation by the market.

In simpler terms, it signifies the advancement of development through the implementation of reforms that confer greater autonomy upon businesses and local governments.

Moreover, Koizumi’s approach was informed by the philosophical concept of “destruction before creation.” During his tenure, the primary obstacles were the extensive bureaucracy and the existence of interest groups. Solve problems by starting with the hardest ones first. The Koizumi government aimed at a critical economic issue, namely the Japan Post, in a prompt and direct manner. Japan Post was a substantial entity, with a workforce of 400,000 employees across 25,000 branches and assets valued at trillions of yen, making it the largest savings institution in the world. Why was it a killer? Japan Post, particularly its banking division, had become a conduit for political financing and related interest groups, burdened with a substantial volume of non-performing loans that exerted a considerable drag on the national economy as a whole.

Koizumi considered the privatisation of Japan Post to be the pivotal element of his proposed reforms(改革の本丸). In order to ensure the passage of the relevant legislation, he took the highly unusual step of dissolving the House of Representatives. Subsequent to the dissolution, the electorate was mobilised to determine the fate of the privatisation of Japan Post, resulting in the ascendance of supporters in the House of Representatives. On 21 September 2005, Koizumi was elected Prime Minister by an overwhelming majority and proceeded to successfully push the legislation through. On 26 September 2006, having fulfilled the objectives he had set himself, Junichiro Koizumi announced his resignation from office.

In addition to the privatisation of Japan Post, Koizumi implemented substantial reforms across a range of areas that challenged the interests of established actors. He investigated non-performing loans in the 1990s, reduced public works spending and government debt by 10%, confronted influential agricultural lobbying groups, social security bureaucracies and medical institutions. This style has also made him regarded as an ‘anomaly’ in Japanese politics. Notwithstanding the criticism levied against his perceived pro-American foreign policy stance, Japan exhibited indications of economic revival in 2006. At that year, the inflation rate approached positive territory, and from 2004 to 2007, the Nikkei 225 index demonstrated a significant increase of over 50%.

However, in the subsequent six years, Japan’s political landscape once again underwent significant upheaval. Following a brief period of recovery, Japan was severely impacted by the global financial crisis of 2008. In 2009, Japan’s GDP contracted by 5.2%, a stark contrast to the global GDP decline of only 0.7% that year. Concurrently, Japan’s exports declined significantly, from $745.6 billion in 2008 to $545.3 billion in 2009, representing a 27% reduction. In 2009, Japan’s nominal GDP was at a level comparable to that of 1991, while the average market value of stocks in the Nikkei 225 index was only one-third of its peak. It is an accurate description to characterise Japan’s economy as being in a state of near-stagnation during this period.

The following section will analyse the policy shifts that occurred following Shinzo Abe’s assumption of office as Prime Minister in 2012. In December of that year, Shinzo Abe, who had previously been a protégé of Junichiro Koizumi, assumed the role of Prime Minister. At that time, few could have foreseen that Abe would emerge as the most influential political figure since the end of World War II, playing a pivotal role in shaping Japan’s economic trajectory.

In February of the following year, Shinzo Abe delivered a speech at the Center for Strategic and International Studies (CSIS) in the United States, wherein he articulated his intention to return to the position of prime minister in order to prevent Japan from slipping into a “second-tier nation.” He said stoutly “Japan is back (日本を、取り戻す).” This statement had two implications. Firstly, Japan needed to develop strategies to counterbalance China’s increasing national power. Secondly, Japan’s aspiration to “return as a first-tier nation” also indicated a desire to reduce its economic and military dependency on the United States.

In the context of considerable anticipation, Shinzo Abe’s “Three Arrows” reform strategy was introduced. The objective of the first arrow was to reform the monetary system, with the goal of achieving monetary expansion and a 2% inflation target through the depreciation of the yen and the implementation of negative interest rates. The second arrow focused on the fiscal system, employing flexible stimulus policies to increase assistance and investment incentives for public works and small and medium-sized enterprises, and stimulate investments with the objective of achieving a budget surplus. The third arrow placed a premium on structural reforms, with the objective of providing support to private enterprises and fostering innovation in order to sustain long-term economic growth. In essence, this means increasing the leading role of government on the basis of monetary expansion and encouraging businesses to innovate and grow.

Following the announcement of the reforms, Japanese society and global investors expressed widespread approval, likening the reforms to a modern “Meiji Restoration” and collectively terming the policies “Abenomics.” The Abe gouverment promptly capitalised on this momentum by launching a ¥10.3 trillion stimulus package and appointing Haruhiko Kuroda as Governor of the Bank of Japan. Kuroda’s task was achieving inflation targets by implementing quantitative easing policies.

The economic policy initiative known as “Abenomics” has had a markedly revitalising effect on the Japanese financial markets. As a consequence of the implementation of the aforementioned reforms, the Japanese yen depreciated significantly against the US dollar. This prompted global investors to acquire Japanese stocks with a total value of 16 trillion yen. In 2013, the Tokyo Stock Price Index (TOPIX) exhibited a 45% surge, while the Nikkei 225 experienced a notable increase from approximately 9,500 points at the conclusion of 2012 to over 20,700 points by July 2015. This represented the highest level observed since 2000. Additionally, Japan’s unemployment rate exhibited a decline, from 4% in the fourth quarter of 2012 to 3.7% in the first quarter of 2013. This was accompanied by a 3.5% increase in consumer spending. Following a period of stagnation, Japan’s GDP demonstrated stable positive growth, while the government debt-to-GDP ratio exhibited a gradual stabilisation.

The remarkable outcomes of the Prime Minister’s policies garnered a noteworthy degree of approval from the Japanese citizenry. Abe’s approval rating increased markedly, reaching 70%. A survey conducted by the Nikkei newspaper(にほんけいざいしんぶん) revealed that 74% of respondents expressed a positive evaluation of the “three-arrow” reforms during that period.

Although the first two arrows reform strategy were rapidly implemented, the third arrow, which emphasises structural reforms for long-term sustainability, remained largely obscured, exhibiting no substantial indications of meaningful advancement.

It is evident that structural reforms inevitably result in the redistribution of various interests and the navigation of power struggles among interest groups. In the face of intractable internal deadlocks, Abe opted for a more indirect approach. In March 2013, the Abe administration announced two pivotal decisions: first,Japan would engage in negotiations to join the Trans-Pacific Partnership (TPP) and second,would also initiate negotiations with the European Union for a Japan-EU Free Trade Agreement. The strategic intent behind these initiatives was evident, namely the promotion of reform through openness. In particular, Abe sought to exploit international agreements as a means of catalysing market-oriented reforms in a range of sectors, including agriculture, energy, health and electricity, with the objective of enhancing Japan’s international competitiveness. This approach shares similarities with China’s strategy of driving reforms through WTO accession.

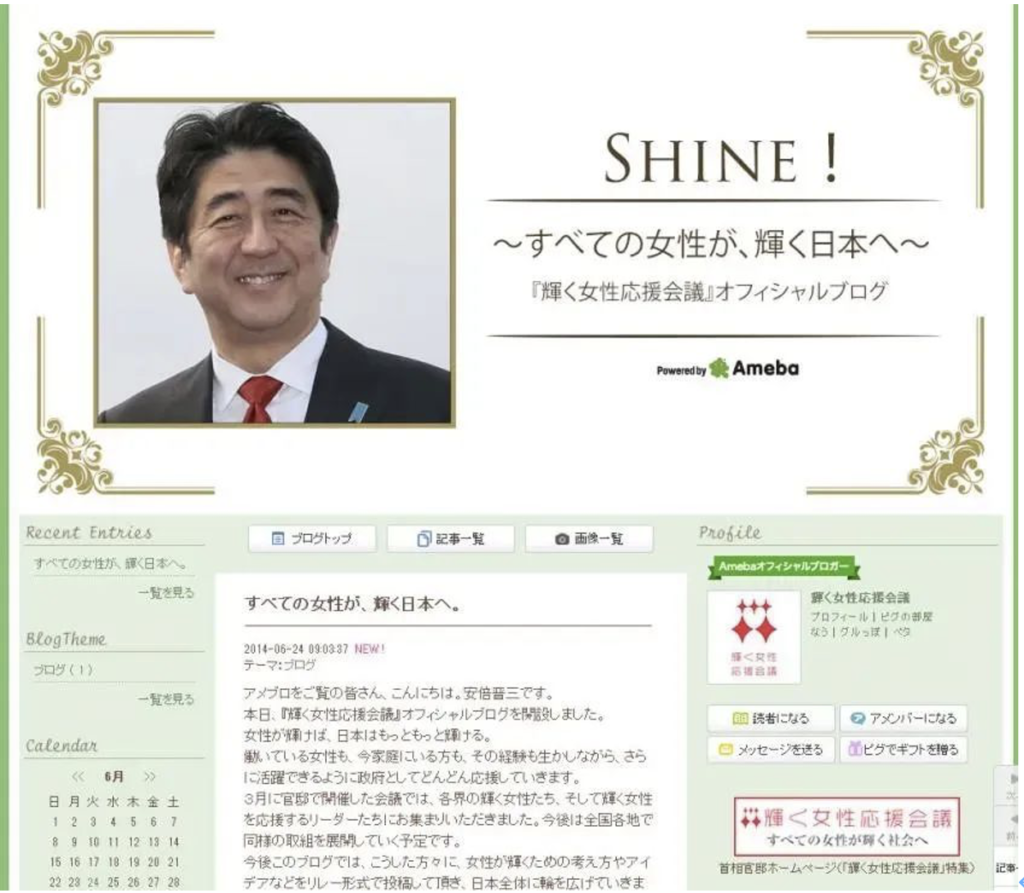

At the Davos Summit in winter 2014, Abe explicitly articulated his intention to “act as a drill bit, breaking through the rock of vested interests and bureaucratic practices in Japan” (ドリルの刃となって岩盤規制を打ち破っていく). This statement highlighted Abe’s resolve to pursue economic reforms. In June of the same year, Abe announced a comprehensive package of reform measures, which the media dubbed “firing a volley of ten thousand arrows”. The aforementioned measures included domestic initiatives such as the expansion of childcare services with the objective of encouraging women to enter the labour market, the reduction of corporate tax rates, and the relaxation of overtime regulations. In terms of external policy, Japan not only eased restrictions on hiring foreign workers but also opened up opportunities in the healthcare sector and facilitated the establishment of businesses by foreign entrepreneurs in Japan.

In September 2015, Abe secured a successful re-election and proceeded to delineate the subsequent phase of governmental emphasis, which he designated “Abenomics 2.0.” The primary objective was to address the demographic challenges facing Japan, namely low birth rates and an ageing population. The goal was to transform Japan into a society where all 100 million citizens can actively participate(1 億人總活躍社會). Additionally, Abe called on Japanese women to work outside the home and integrate into society. In his blog, he stated, “Let us encourage all women to flourish, and together, propel Japan towards a more radiant future.”

Furthermore, Abe set forth ambitious and precise targets for the new “three-arrow” reforms, which included attaining a GDP of ¥600 trillion by 2021, raising the national fertility rate from 1.4 to 1.8, and stabilising the population at 100 million. This demonstrates that the reform agenda has expanded to encompass social objectives in addition to economic ones.

Nevertheless, the success of Abe’s policies on women during this tenure is not without question. While several initiatives have been effective in mobilising women, as evidenced by the increase in the proportion of female working population from 60% to 70% between 2012 and 2020, significant challenges remain. Although women are mobilized, opportunities for women to choose from have not expanded substantially. Indeed, a majority of women still hold part-time or non-regular positions.

In particular, within the public sector, by 2020, no tier of the Japanese government, ranging from local municipalities to prefectures and up to the central government, had attained the established goal of achieving 30% representation of women in positions. Even the most open-minded Senate, women accounted for only 22.9% of representatives in 2020. In the House of Representatives, women constituted a mere 10% of representatives, which places Japan among the countries with the lowest female parliamentary representation globally. Local government statistics were similarly discouraging, with female leaders accounting for a mere 1% to 4%.

In recent years, the impact of Covid-19 has led to significant challenges for many service industries, resulting in a notable increase in layoffs. These developments have had a particularly adverse effect on women, who are disproportionately represented in part-time positions and have consequently been more severely affected by the job losses. These setbacks have impeded the advancement of social reforms. As indicated in the World Economic Forum’s Global Gender Gap Report in 2023, Japan was ranked 125th out of 146 countries globally, representing a decline of 24 places from its 2010 position of 101st. Consequently, Japan has experienced a gradual decline in its fertility rate since 2015, reaching 1.367 in 2023. It is evident that the Abe government miscalculated the power of intertia law of social development, and its series of social reform policies have struggled to achieve the desired impact.

In conclusion, both Koizumi and Abe pursued a strategy of “reform to promote growth,” with the objective of addressing Japan’s fundamental issues. Notwithstanding the difficulties they encountered, their endeavours proved pivotal in identifying deficiencies and implementing efficacious solutions. However, neither leader was ultimately able to achieve their overarching objectives. Zhou Zhanggui, Chief Advisor at Sinnvoll Consultancy, posits that Japan’s reform is not a panacea, a lot of work and China’s reform and opening-up strategy is closer, but also in Japan’s weak control system borrowed from China’s successful experience. Nevertheless, two key considerations emerge. Firstly, Japan’s market economy, adherence to the rule of law, globalisation, and robust corporate governance effectively foster investor and entrepreneurial confidence through consistent policies. Secondly, Japan’s adaptive and constructive approach in managing relations with major global markets is worthy of note. In conclusion, the critical lessons highlight the importance of leveraging the market economy and establishing a stable international environment.

Nevertheless, it is irrefutable that the reforms initiated by both prime ministers have established a pivotal foundation for Japan’s contemporary economic prosperity.

Outlook: Japan’s economy enters a new era.

The signs of recovery from Japan’s current economic boom are more obvious this time around, and as a barometer of the economy, the stock market has been showing the signs of recovery to the full.

Behind such a boom, the geopolitical changes that have occurred in recent times have played a pivotal role in reshaping Japan’s national trajectory. From the strategic rivalry between China and the United States to the 2022 Russia-Ukraine conflict, the global landscape has transitioned from being quiet to becoming more complex. Japan has emerged as a beneficiary amidst this competition.

In 2023, Warren Buffett, the renowned American investor, shifted his focus to Japan, publicly expressing optimism about the Japanese economy. He adheres to the conviction that “20 years, 50 years later, both Japan and the United States will be stronger than they are now.” He regards investing contrarily in Japan as the optimal hedge against the US market. Berkshire Hathaway, the investment vehicle of Warren Buffett, increased its holdings in Japan’s five largest trading houses, namely Itochu Corporation, Marubeni Corporation, Mitsubishi Corporation, Mitsui & Co., Ltd., and Sumitomo Corporation, to 7.4%.

In close succession was Larry Fink, the Chief Executive Officer of BlackRock, the asset management company, who also visited Tokyo. During a roundtable meeting with Japanese Prime Minister Fumio Kishida, Fink observed that Japan is well-positioned to replicate the economic miracle of the 1980s during its current economic transformation. He also expressed confidence that this miracle could be sustained for an extended period.

Mr. Zhou, the Chief Consultant at Sinnvoll Consultancy, presented a comprehensive analysis of the factors contributing to Japan’s economic resurgence, as follows:

The macroeconomic environment has begun to exhibit favourable characteristics for Japan. At the present time, the intensified strategic competition between the United States and China, along with the complex relationship between the European Union and China, has served to enhance Japan’s appeal, particularly investments in areas of sensitivity such as semiconductors, AI, and new energy vehicles. Furthermore, the restructuring of regional industrial chains has resulted in particular industrial advantages for Japan.

From Japan’s internal environment, the concept of “reform promoting growth” has become firmly established and is beginning to yield results. While the Kishida government, which succeeded the Koizumi and Abe eras, did not introduce a uplifting reform programme, its commitment to economic reform, particularly the pivotal transition from savings to investment, represents a pragmatic approach to Japanese reform. Subsequent practical measures, such as leveraging foreign capital, stimulating initially the capital economy and real estate sectors, followed by unleashing Japan’s societal potential, have been pivotal in driving the current economic prosperity.

The Kishida administration is pursuing a series of reforms with considerable vigour. To illustrate, the government has initiated improvements to the shareholder investment environment with the objective of enhancing the appeal of Japan’s stock market. A significant challenge currently facing Japan’s securities market is the persistently low price-to-book ratio, with the majority of Japanese companies currently exhibiting a P/B ratio below 1. This situation is not primarily attributable to financial weaknesses within Japanese companies; in fact, 50% of these firms maintain a “net cash” position, where cash reserves exceed liabilities. However, as a consequence of the asset bubble that occurred in the 1990s, there has been a prevailing tendency among companies to prioritise savings over expenditure.

In order to stimulate corporate investment, Japan has initiated a campaign, entitled “Emptying the Treasury”. In the spring of 2023, the Tokyo Stock Exchange issued warnings to approximately 3,300 companies, urging them to enhance shareholder value and adjust financial strategies in accordance with the aforementioned recommendations. In accordance with the prevailing regulations, companies are obliged to achieve a price-to-book ratio in excess of 1 and a minimum return on equity of 8%. In order to avoid delisting, firms are left with two viable options. The first option is to “spend,” which involves investing in research and development, initiating new business operations, or expanding the workforce to improve these metrics. The second option is to “pay out,” such as through stock buybacks or increased directly dividends, to bolster shareholder returns. There’s nothing else to do. In the autumn of 2023, the Tokyo Stock Exchange once again issued warnings to companies. Concurrently, the Japanese government is promoting tax incentives with the objective of encouraging affluent individuals to utilise their personal savings for investment purposes.

After the ‘Emptying the Treasury’, Japan began to adjust the economy to more structural problems, and the following three things were considered to be the top priorities.

Firstly, in the near term, the growth of wages is the most critical factor. Notwithstanding the Japanese government’s projection in the “2024 Economic Outlook Report” that inflation will exceed 2% in succession over the next three years, the persistence of challenges such as wage increases and subdued demand represent significant barriers to overcoming deflation. A field survey conducted by the Sinnvoll Consultancy in Japan in November 2023 revealed that nominal wages increased by less than 1% from 2022 to 2023. This is in stark contrast to the inflation rates of 3.2% in 2022 and 3% in 2023. Consequently, Japanese workers effectively encountered a de facto decrease in wages, which contributed to a decline in consumer demand.

Olivier de Berranger, the Chief Investment Officer at La Financière de l’Echiquier, has highlighted, “all this monetary and fiscal effort will be worthless unless wages rise accordingly”. Japan’s largest labour union federation, RENGO(連合), is preparing for its annual wage negotiations in spring 2024, with the objective of achieving a 5% increase. However, from the perspective of Japanese employers, achieving this magnitude appears somewhat implausible, especially considering that cumulative production price increases over the next three years are projected not to exceed 4%. Moreover, while major Japanese corporations have consented to successive wage increments, small and medium-sized enterprises, which account for 70 per cent of employment in Japan, have adopted a cautious stance. In light of the aforementioned considerations, the outlook for wage increases in 2024 remains uncertain at this juncture.

Secondly, in the short to medium term, in order for the Japanese economy to achieve positive growth, it must capitalise on the current opportunity for a rebound in demand. A pivotal element of this strategy is the assurance of a sufficient workforce, comprising both intellectual and manual capabilities.

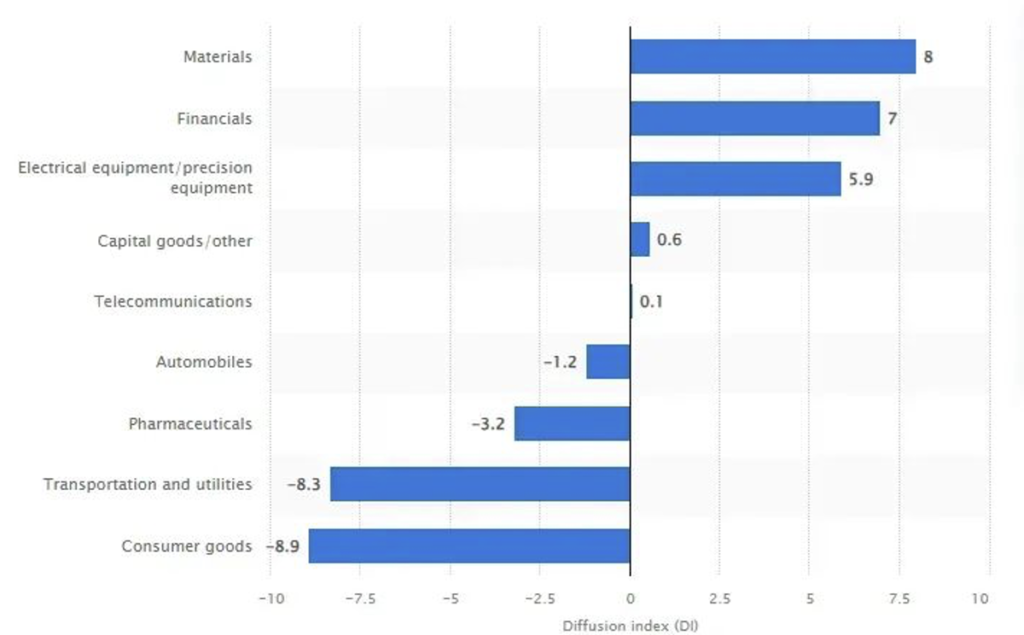

The Diffusion Index of Employment Conditions (DI), as observed over the short term by the Japanese Ministry of Economy, Trade and Industry in December 2023, has demonstrated a consistent decline into negative territory. This indicates that Japan is currently experiencing a notable shortage of labour in a range of sectors, particularly in tourism-related industries such as catering, accommodation and transportation.

A survey conducted by the Teikoku Databank during the first half of 2023 among 27,663 companies nationwide revealed that 75.5% of hotels and lodging establishments reported a shortage of regular employees. Furthermore, 78% of related enterprises cited a lack of casual workers, which was the second highest percentage following the restaurant industry. Furthermore, popular tourist destinations such as Tokyo, Osaka, and Kyoto frequently observe the presence of lengthy queues of passengers awaiting the bus. In the Hakone region, the number of taxi have already been increased by 50% in order to meet the demands of the tourist industry. However, the prevailing circumstances indicate that, at least, an additional 50% increase is required to adequately accommodate the sustained inflow of tourists. Meanwhile, at Osaka International Airport, the average security wait times from November to December 2023 reached three hours per person, highlighting the significant challenges currently facing Japan’s transportation sector.

The Japanese government and relevant industry sectors are proactively addressing these challenges by expanding training opportunities to enhance the workforce, particularly for foreign workers. According to the survey conducted by the Sinnvoll Consultancy in Japan in November 2023, it revealed that young individuals from Southeast Asia and South Asia have become the primary part-time workforce in convenience stores, restaurants, and hotels. Nevertheless, this has not been sufficient to alleviate the labour pressures that are prevalent in the industry.

The underlying causes of these challenges remain unchanged due to Japan’s ongoing demographic issues, namely low birth rates and an ageing population. The data of Japanese Cabinet Office has revealed that in 2022, Japan’s net population increase fell below 800,000, with the number of individuals aged 65 and older reaching 46 million, representing 36.3% of the population. This underscores Japan’s constrained capacity to leverage opportunities for growth in tourism and consumer recovery, thereby markedly expanding economic prospects.

Thirdly, in the medium to long term, it is essential that Japan’s industries receive the sufficent support.

In comparison to the accelerated growth witnessed in India and Mexico over the past two years, Japan’s industrial framework currently didn’t exist the capacity for rapid expansion “from the ground up.” Furthermore, in comparison to Hungary, Japan’s industries, particularly the automotive manufacturing sector, encounter significant challenges in rapidly transitioning to fully develop electric vehicles or battery industry chain. Where do the potential avenues for growth exist for Japan’s industries? This is a question that requires further investigation.

Over the past three decades, although Japan has lost many technological competitions to Chinese as well as American companies, it has preserved considerable strength in many industries. To illustrate, Kawasaki Heavy Industries, a company with a reputation for manufacturing motorcycles, has expanded its operations to encompass mechanical manufacturing and the aerospace sector. Kawasaki has made considerable investments in hydrogen energy research and development, encompassing various stages of the value chain. Although these initiatives have yet to yield profits, they illustrate promising potential for future growth and innovation.

Furthermore, the Japanese materials industry, electrical equipment sector, precision instruments industry, and electronic components industry continue to demonstrate considerable potential for growth. This is primarily due to two key factors. Firstly, Japan has a robust foundation in these sectors, with numerous companies, including many small and family-owned enterprises, specialising in and innovating specific technologies over the long term, and achieves a breakthrough. To illustrate, Maruwa, a company specialising in the production of heat-resistant ceramic components, has observed an increase in the utilisation of its ceramics in AI servers and electric vehicles. This growth can be attributed to technological advancements and the expansion of applications. An additional case in point is Nifco, a supplier of automotive parts, initially focused on the production of plastic fastener components, but given that this company produces superbly crafted carabiners that are guaranteed to stay on for years, the volume of orders has risen steadily in recent years.

It is worthy of note that, in the context of the strategic competition between China and the United States, a significant number of Japanese companies have adopted a strategy of relocation. The semiconductor sector, renowned for its sensitivity, was first to react, with Sony and Kioxia relocating to Kitakami City, Iwate Prefecture, and Kumamoto Prefecture in Japan in June 2022. These relocations are expected to invigorate local industries. However, the impetus for further industrial advancement is significantly constrained by the dearth of new investors.

In light of these findings, it can be concluded that Japan has indeed emerged as a safe haven for global investors seeking refuge. Nevertheless, Japan is confronted with its own social issues and constraints with regard to industrial development. In considering Japan’s economic growth trajectory over the long term, it becomes evident that there is a notable absence of sustained momentum, which underscores the necessity for continued observation.

Although the rationale for long-term optimism in Japan may currently be insufficient, it is crucial to acknowledge the efficacy of Japan’s “reform and openness” policies. It is evident that Japan’s economy is entering a new phase, which serves to underscore its significance for those investors who adopt a prudent approach.

In the estimation of the late Professor Masahiko Aoki of Stanford University, the process of transitioning from Japan’s current state to a novel institutional system will require approximately 30 years. Professor Aoki identified 1993 as the commencement of this cycle, because in that year, there was a collapse of Japan’s bureaucratic system. Accordingly, 2023 represents the conclusion of the aforementioned 30-year period. Nevertheless, for Japan’s economy to regain its former 20th-century prestige, it will likely require further reforms and sustained assistance from both domestic and international sources. It is insufficient to rely on business and affluent class savings as a means of sustaining Japan’s long-term prosperity.

It seems inevitable that Japan’s transition into a new economic phase will have an impact on the global expansion strategies of Chinese multinational corporations. The following section presents a summary and conclusion.

Firstly, there are few countries in Asia that can be considered to possess a combination of robust purchasing power, substantial industrial and market size, and a conducive business environment. Despite exhibiting strong consumer purchasing power, Singapore and Hong Kong are relatively small in scale, with a combined population of only 13 million. Although markets such as India, Vietnam, and Indonesia have large populations and promising growth potential, they do not match Japan’s mature market in terms of purchasing power and overall business environment.

Secondly, in contrast to consumers in the United States and Europe, Japanese consumers typically exhibit a rational consumer mindset, characterised by a trend towards “denationalisation. This aspect assumes heightened importance in the contemporary context, amidst shifts in international geopolitics that suggest a resurgence of historical nationalist sentiments in the United States and Europe. Consequently, consumers in these regions, whose values may be a factor in their purchasing decisions, may demonstrate a reduced inclination to purchase Chinese products. From this perspective, there has been no significant change in Japanese consumer preferences towards Chinese products following the pandemic and the Russia-Ukraine conflict. The majority of Japanese consumers continue to prioritise product performance over national origin. In recent years, a number of brands, including Haier, Hisense, Lenovo, and several local successes such as MIXUEBINGCHENG, Lemon8 (under ByteDance), and Florasis, have managed to establish a significant presence in the Japanese market.

Thirdly, there is an increasing convergence in consumer behaviour among young people in China and Japan. The consumption patterns of youth in both nations exhibit striking similarities. They share a preference for using social media and lifestyle apps to keep abreast of current trends, frequently utilising these platforms to seek out popular online stores and to consistently discover new and intriguing destinations. Consequently, numerous marketing strategies that prove effective in China can be effectively adapted for success in Japan.

Ultimately, as the value of the Japanese yen declines and the prospect of expansive monetary policies on the horizon, operational expenses in Japan are progressively diminishing. In contrast to Western Europe and the United States, where inflation rates are higher, labour costs in Japan are in decline. Furthermore, Japanese employees are accustomed to the work culture prevalent in East Asia, which contributes to comparatively lower operational pressures during the later stages of business operations.

In light of the aforementioned points, it is evident that Changes in the Japanese economy in the new era have created a favourable opportunity for globalisation among Chinese enterprises. Excluding extreme conditions of political uncertainty, Japan has emerged as a pivotal destination for Chinese firms seeking to gain a foothold in high-end international markets.

Mr. Zheng Lei, a distinguished consultant invited by Sinnvoll Consultancy with 20 years of specialisation in the Japanese industry, observed that the current economic recovery in Japan is significantly bolstered by the extensive overseas experience accumulated by Japanese companies. In the aftermath of Japan’s economic downturn years ago, these firms embarked on a collective overseas expansion to find new work chance. They are often referred to as “pioneers of the new continent”, laying the foundation for subsequent economic revitalisation. The courage, experience, and insights gained from this endeavour offer valuable lessons for Chinese enterprises. It is therefore critical for Chinese enterprises to establish a robust presence and thrive in the global market, a goal that can only be achieved through thorough research.

In conclusion, as per Song Xin, founder of Sinnvoll Consultancy, a historical review of the Japanese economy reveals the impact of “reform for growth” policies pursued by successive Japanese governments. These policies have gradually revealed the potential and opportunities within Japan’s economy. Concurrently, Japan’s reform initiatives and historical resilience in recovering from economic downturns are of significant relevance and offer valuable lessons for China. Given the similarity in the logic of the economic rise of the two countries and the commonality of the challenges they face today. Japan’s successful economic revival serves as a valuable benchmark for China. It is of particular significance to examine Japan’s strategies for overcoming deflation and achieving renewed growth. It is currently unproductive to focus unduly on Japan’s so-called “lost thirty years”. Conversely, it would be prudent to adopt an open-minded approach to re-examine Japan’s economic landscape, foster pragmatic collaboration and address competitive challenges.

In order to gain a comprehensive understanding of the circumstances and developments in neighbouring countries, it is essential to adopt a composed and objective stance, coupled with a spirit of humility and prudence. This approach enables the transcendence of emotional biases and the attainment of profound insights and substantial benefits. When formulating strategies for major powers, objectivity and rationality are of the utmost importance.

Reference

- 1. Japan – wo das Geld in Strömen fließt, Thomas Mersch and Stefan Merx, 20/12/2023, manager magazine 1/2024

- 2. At Last, It Seems Japan Is Winning Investment Fans, Tom Burroughes, 28/07/2023, WealthBriefing

- 3. Japan: Can It Emerge From Decades-Long Deflation?, Amanda Cheesley, 08/11/2023, WealthBriefing

- 4. European Economic Forecast Automn 2023, 11/2023, European Commission

- 5. Japan’s stockmarket rally may disappoint investors, 08/06/2023, The Economist

- 6. 『「不動研住宅価格指数」10月値の公表について』,26/12/2023, 日本不動産研究所

- 7. The Japanese Economic Miracle, 26/01/2023, Berkeley Economic Review

- 8. 『戦後日本経済と経済同友会』, 岡崎哲二、菅山真次、西沢保、米倉誠一郎,1996, 岩波書店

- 9. 『新NISA元年 「みんなの株式市場」が始まる』,30/12/2023, 藤田和明, 日本经济新闻

- 10. 《对话经济学家辜朝明:一代人经历衰退,一代人重拾信心》,龚方毅、黄俊杰,20/07/2022, LatePost

- 11. 《物价连涨3年,日本走出通缩了吗?》, 29/12/2023, 日经中文网

- 12. Lessons from the Japanese Miracle: Building the Foundations for a New Growth Paradigm, 09/02/2015, 岡崎哲二, nippon.com

- 13. Inbound tourists drive Japanese department store sales to record high, CHIHIRO ISHIKAWA, 02/01/2024, Nikkei Asia

- 14. Reinterpreting the Japanese Economic, Miracle, Robert J. Crawford, 1998, Harvard Business Review

- 15. How Did Koizumi Cabinet Change Japan?,Komine Takao, 05/06 2007, Japan Spotlight

- 16. Why Koizumi’s ‘It’s Now or Never’ shtick fell flat, William Pesek, 26/04/2021, Nikkei Asia

- 17. 20 years after Koizumi: How Japanese politics were restructured, MASATO SHIMIZU, 16/04/2021, Nikkei Asia

- 18. Global Gender Gap Report 2023, Insight Report, 06/2023, World Economic Forum

- 19. EDITORIAL: Women can only ‘shine’ in society when their rights are respected, 10/09/2020, The Asahi Shimbun

- 20. Shinzo Abe Vowed Japan Would Help Women ‘Shine.’ They’re Still Waiting, Motoko Rich and Hisako Ueno, 13/09/2020, The New York Times

- 21. Warren Buffett says he intends to add to Japanese stock holdings, MAKOTO KAJIWARA, KAZUAKI FUJITA and MITSURU OBE, 11/04/2023, Nikkei Asia

- 22. BlackRock’s Fink Sees Echoes of 1980s Miracle in Japan, Isabel Reynolds, 06/10/2023, Bloomberg

- 23. More foreign tourists, worker shortages fuel tourism troubles,20/06/2023, The Asahi Shimbun

- 24. The legacy of Abe Shinzo will shape Japan’s economy for years, 14/07/2022, The Economist

- 25. Japan manufacturers exit China, Southeast Asia to bring production back home, 16/05/2022, SCMP

- 26. 《失去30年,日本终于要向上了?》,藤田和明, 17/08/2023, 日经中文网