Brazil, a vibrant and dynamic country, is situated in the distant South America. As the fifth-largest nation and ninth-largest economy globally, Brazil is renowned not only for its Carnival, samba, and football, but also for its substantial market potential and geopolitical advantages. In recent years, Brazil has emerged as a pivotal destination for more and more Chinese enterprises seeking to expand their global footprint.

It appears that the electric car industry has become the epitome of Chinese companies’ penetration of the Brazilian market. According to data from Fenabrave, BYD accounted for 74% of electric vehicle sales in the first quarter, while Great Wall Motors secured a 12% share, making it the second most popular brand. In order to consolidate their position in the Brazilian automotive market, which is the sixth largest in the world, and to circumvent the policies of the Lula’s government, Chinese car companies are also engaged in a battle for manufacturing exports.

In March 2024, BYD formally initiated operations at its manufacturing facility in São Paulo and announced plans to commence production by mid-2025. In response to BYD’s accelerated progress, Great Wall Motors announced in early May that its Brazilian factory would commence production by the end of the year. Moreover, in mid-May, Zhejiang Leapmotor announced the launch of a new model in Brazil, developed in collaboration with the European automotive giant Stellantis.

These major automotive brands, which typically engage in competitive activities on the global stage, are simultaneously expanding their operations in Brazil. This is creating an unusual competitive landscape and underscoring the strategic significance of Brazil for Chinese new energy vehicle manufacturers. It is worth noting that BYD takes over a factory previously operated by Ford of the United States, while Great Wall Motors acquired a plant formerly run by Mercedes-Benz of Germany. This transition indicates a shift in the dominant players in the automotive industry, with the withdrawal of traditional brands underscoring the growing prominence of Chinese car manufacturers.

Chinese companies are actively expanding into the Brazilian market not only in the field of electric vehicles, but also in areas such as cross-border e-commerce and consumer electronics. The fashion retail platform Shein has achieved a notable degree of success in Brazil, ranking 29th in the SBVC’s top 500 rankings, surpassing numerous global brands. In order to reinforce its market position, Shein has announced an investment of $150 million in Brazil in 2023, with the objective of achieving 85% degree of localisation by 2026. Furthermore, Temu is scheduled to enter the Brazilian market in the current year, benefiting from a $50 import tax exemption policy enacted by the Brazilian government.

Over the past five years, the global geopolitical landscape has undergone a series of persistent shifts, particularly as a result of the intensification of Sino-U.S. strategic competition and the growing complexity of the China-EU relationship. On one hand, these dynamics have rendered international expansion more challenging for Chinese companies and on the other, disrupted their previous patterns of overseas growth. In this context, Brazil, situated a considerable distance from both China and the United States, has emerged as another significant destination for Chinese firms pursuing global expansion.

In this article, Sinnvoll Consultancy will examine the Brazilian market from three perspectives, drawing on its extensive experience in monitoring the Latin American market and based on a synthesis of literature review and industry research. This article is composed of three parts: Historical Exploration: From Portuguese Colony to Brazilian Empire, Economic Analysis: Falling into the Middle-Income Trap in the midst of turmoil, and Market Insights: The Virtual and Real Opportunities in the Brazilian Market.

The objective of our research is to gain insight into the rationale behind the decision of Chinese enterprises to expand their operations into Brazil. By analysing the factors that influence this decision, it is hoped that Chinese enterprises will be better equipped to navigate the Brazilian market and avoid potential pitfalls, thereby laying the foundation for the successful implementation of their globalisation strategies.

Historical Exploration: From Portuguese Colony to Brazilian Empire

The Portuguese Empire exerted a profound and pervasive influence on Brazilian society throughout its history. The analysis of Brazilian history presented by the Sinnvoll Consultancy commences with an examination of this country’s involvement.

The relationship between Portugal and Brazil is characterised by a long-standing and intricate web of connections. The initial Portuguese colonisation of Brazil was violent and exploitative. Throughout Brazil’s struggle for independence, a complex series of conflicts and compromises occurred between the two parties. Despite the eventual achievement of independence in Brazil, the traumatic past remains a deeply ingrained aspect of the country’s collective memory.

The phenomenon in question had its origins in the 15th century, during Europe’s Age of Discovery. Portugal, Spain, England, France and the Netherlands initiated the expansion of global trade routes through maritime exploration, at the same time, they established colonies worldwide. In order to discover a new route to India, Manuel I de Portugal dispatched the explorer Pedro Álvares Cabral on a voyage of discovery.

On 22 April 1500, the Portuguese ships arrived in the vicinity of Bahia on the eastern coast of Brazil. They were shocked by what they saw. “The landscape is characterised by extensive forests comprising reddish-brown trees and luxuriant foliage. The indigenous population exhibit brown skin with a reddish hue, and their facial features and noses are notably attractive. They are unclothed but display no indications of shame. It seems reasonable to conclude that these individuals are comparable to birds or beasts, yet their bodies are remarkably clean and robust. The area is rich in yams, seeds, and fruits.”

At that time, Brazil was inhabited by approximately 2,000 indigenous tribes. The indigenous tribes were largely powerless to resist the Portuguese conquerors. The Confederação dos Tamoios of 1554 was unable to effectively counter the Portuguese military forces, which were equipped with firearms and cannons. As a result, the Portuguese established colonial rule over Brazil.

In comparison to the remote and sterile Portuguese landscape, Brazil was characterised by a greater degree of natural wealth. The Creator bestowed upon it a plethora of bountiful natural resources, which should have been a blessing for the indigenous people became a curse because of Portugal’s greed. Portugal’s occupation of the land was accompanied by the plundering of natural resources. In particular, a reddish-brown tree, highly prized by the colonisers and known as “pau-brasil,” and the land being gradually referred to as “Brasil” by the colonisers.

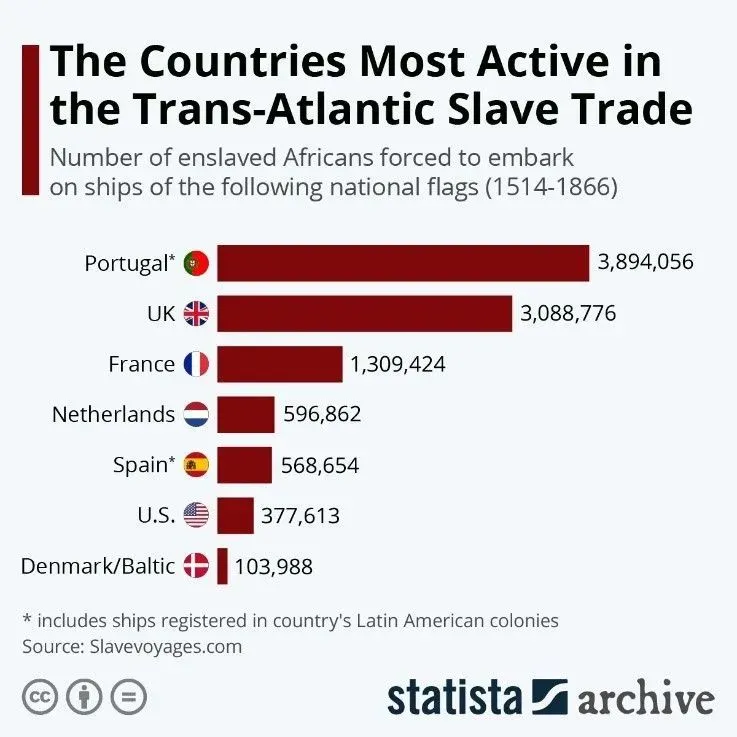

Nevertheless, the felling of trees marked merely the begin of “A maldição dos recursos naturais” in Brazil. As Europe’s demand for sugar and cotton increased, the Portuguese colonisers were pleased to discover that the soil and climate of the north-eastern region were conducive to the cultivation of these crops. They rapidly established engenhos. To address the labour shortage, the King of Portugal implemented a dual strategy. Firstly, he sent significant numbers of European men to enslave native peoples in the local area. Secondly, he initiated the introduction of black slaves from Africa. In the late fifteenth century, Prince Henrique, o Navegador of Portugal, arrived in Africa, in exchange for sugarcane and other items, he acquired a large number of Negro slaves from local African Negro traders and transported them to South America. Historical statistics indicate that Portugal was the nation with the most extensive slave trade in history, with a total of 3.2 million slaves transported to Brazil.

The lucrative sugarcane industry also attracted the Dutch and the French. In the mid-16th century, French colonisers established a colony and exerted control over the region between Rio de Janeiro and Cabo Frio. In the early 17th century, the Dutch established a colony in Recife and initiated the cultivation of sugarcane. However, both the French and Dutch colonisers were ultimately compelled to withdraw as a consequence of defeats at the hands of Portuguese forces and the sustained resistance of enslaved people. This resulted in Portugal becoming the dominant power in the region.

However, the prosperity of the sugarcane industry was ephemeral. The Dutch East India Company, operating from India, initiated a large-scale programme of sugarcane cultivation utilising forced labour. This resulted in a significant increase in global sugarcane production and a notable decline in sugar prices, which rendered Portugal’s investment in Brazil for sugarcane cultivation unprofitable. In response, the Portuguese withdrew from the exhausted sugarcane lands and shifted their focus to a new target: coffee beans.

Following the introduction of coffee beans to Brazil by the Portuguese explorer Francisco Palheta, the Portuguese began cultivating coffee in the regions of Rio de Janeiro, São Paulo, and Minas Gerais. Brazilian coffee beans were soon exported on a global scale. By 1820, Brazil had overtaken Java in Indonesia to become the world’s foremost coffee producer. By 1850, Brazil was responsible for approximately 50% of global coffee production.

While the cultivation of sugarcane, cotton, and coffee had already made Brazil an increasingly attractive destination for Portuguese colonists, the subsequent gold and diamond rushes incited even greater fervour. By the late 17th century, substantial gold deposits were discovered in the Minas Gerais region of southeastern Brazil, resulting in a significant influx of immigrants from Portugal and other colonial territories. In the early 18th century, diamond deposits were discovered in the vicinity of the village of Tijuco, which attracted the interest of other European nations eager to exploit these resources. This resulted in considerable competition for mineral resources in Europe. In order to establish a monopoly over the diamond mining industry, the Portuguese Crown imposed a strict ban on trade between Brazil and other countries.

However, as Portugal’s influence in Europe declined, particularly in its trade with Britain, Tratado de Methuen was signed in 1703. At that time, the Portuguese government sought to gain access to the British market for its wine, and consequently agreed to open both its domestic and colonial textile markets.

Nevertheless, the British were not primarily interested in Portuguese wine; their primary focus was on Brazil’s gold and diamonds. British textiles, renowned for their cost-effectiveness, rapidly became the preferred option among miners. In the latter half of the 18th century, Britain’s industrial prowess further consolidated its dominance in the textile industry, precipitating the collapse of Portugal’s textile sector and Brazil, as its colony, was transformed into a market for British surplus goods. As a result, Britain accrued substantial profits, with records indicating that over five tons of gold were shipped to London each week.

The British pushed Brazil into the abyss of poverty. By the conclusion of the 18th century, as the exploitation of gold and diamonds reached its conclusion, the Brazilian economy was in a state of greater privation than that which had existed prior to the commencement of these mining activities. As documented in A Tragédia da Renovação Brasileira, “madmen and hungry people everywhere, even thirteen-year-old prostitutes”.

Against this backdrop, Brazil experienced a pivotal moment in its history: the declaration of its independence. In the early nineteenth century, as Napoleon’s armies advanced across Europe, King João VI of Portugal, acknowledging the severity of the circumstances, relocated to the Brazilian colony and established Brazil as a union on par with Portugal. In 1820, the monarch returned to Lisbon, appointing his son, Pedro de Alcântara, as regent in Brazil. But surprisingly, Pedro not only defied his authority but also aligned with Brazilian nationalists. On 7 September 1822, following the declaration of “Independência ou Morte!”, Prince Pedro proclaimed Brazil’s independence and ascended to the imperial throne as Dom Pedro I of Brazil. Despite his indignation, King João VI was ultimately unable to sustain military conflicts overseas and was compelled to recognise Brazil’s sovereignty in 1825.

It can be said that Brazil’s colonial history began and ended with the Portuguese. In contrast to the violent revolutions that occurred in other Spanish colonies, Brazil, under the governance of Dom Pedro I and his son Dom Pedro II, managed to avoid significant bloodshed despite experiencing a series of military coups. What’s more, it gradually transitioned towards parliamentary monarchy reforms over nearly half a century, thereby inaugurating a period of peaceful development and prosperity. During this period, Brazil emerged as the foremost exporter in Latin America, with exports increasing as a consequence of technological advancement. Furthermore, Brazil commenced the construction of ports and railways at an earlier stage than many European countries. By 1890, its per capita income had reached $770.

Mr Zhou Zhanggui, Chief Consultant at Sinnvoll Consultancy, points out that during this period, many Japanese immigrants moved to Brazil to escape the war. At the time, based on this historical background, Brazil remained a prosperous and stable nation, serving as a haven amid global turmoil. However, the subsequent large-scale return to Japan of Japanese immigrants also reflects the fluctuating living conditions in Brazil during this period.

This history is a perspective for understanding Brazil, seeing its early years as a gradual stabilization in the midst of intense turmoil. It also establishes a foundation for understanding the complexities of modern Brazilian society. It’s a crucial historical context for Chinese multinational corporations to examine.

Economic Analysis: Falling into the “Middle-Income Trap” in the midst of turmoil

Brazil, originally endowed with natural advantages and abundant resources, was positioned to emerge as a major power. It is unfortunate that the country’s development path has not been smooth.

The analysis conducted by Brazilian economist João de Scantimburgo indicates that had the Brazilian Empire maintained its developmental speed, per capita income in Brazil would have reached a level comparable to that of Western European countries by 1950.

However, the fortunes of Brazil underwent a distinct transformation. At the same time that Brazil was making progress, a significant external factor emerged in its recent history: the United States. And the military came to play a central role in Brazilian politics.

At that time, South America had already experienced a period of significant political upheaval, with numerous colonies declaring their independence and establishing republican governments. The Brazilian Empire was a notable exception to this trend. The United States sought to encourage a republican revolution in Brazil with the objective of strengthening economic ties and extending its influence in the Western Hemisphere.

In 1889, General Deodoro da Fonseca, with the support of the United States, initiated a military coup that resulted in the proclamation of Primeira República do Brasil. The United States was the first country to recognise the new government and establish diplomatic relations with it.

The sudden coup also completely disrupted Brazil’s economic development. In the context of the Primeira República do Brasil, the political elections became a means of exerting power, dominated by oligarchs from the coffee plantation sector. The presidency was monopolised by São Paulo’s coffee magnates and Minas Gerais’ dairy barons, who implemented policies favourable to their respective industries. This was known as the “política do café com leite”. The aforementioned power struggles among vested interests impeded the promising growth of the industrial sector. In response to market demands from Europe and the United States following the industrial revolution, Brazilian estates produced only exportable goods, resulting in a significant reliance on imported foodstuffs (75% of domestic supply).There was a notable shift in the composition of exports, with a transition from a diversified profile to a more homogeneous one, this kind of “Latifúndio economies” laying the foundations for the collapse of coffee prices in the 1920s.

In the subsequent decades, Brazil’s political landscape remained highly unstable, undergoing six system changes in total. Externally, there was the close concern of the United States, and internally, there was the disruptive involvement of the military.

In 1930, internal conflicts among oligarchic factions over the electoral process led to the intervention of the military and the formation of a provisional government. In 1937, with the support of the military, Getúlio Vargas seized power and established the dictatorial Estado Novo regime. By 1945, with the support of the military, Brazil had reverted to a democratic republican system of government.

The country’s ongoing political and social turbulence has contributed to a significant exacerbation of the already alarming rates of poverty in Brazil. Despite adopting an “isolationist policy” and avoiding significant impacts from World War I and World War II, Brazil failed to achieve economic and societal development; instead, it regressed. To illustrate, the ambitious state-owned steel project of the 1930s-1940s, Companhia Siderúrgica Nacional, encountered slow progress due to inadequate external funding and technological support. By the time of the conclusion of World War II in 1945, Brazil’s industrial capacity was already outdated.

In 1964, the implementation of socialist policies by left-wing President João Goulart gave rise to discontent among conservative and military factions in Brazil. The White House expressed support for the military’s overthrow of the government, citing concerns about the perceived socialist threat and assisting General Artur da Costa e Silva as the new President. This event marked the beginning of a period of dictatorship that endured for over twenty years, until 1988, coinciding with the end of the Cold War era. The New Constitution has been established and it placed an emphasis on the separation of powers, reinforced the authority of the civilian government, and curtailed the influence of the military. Subsequently, Brazil was able to reestablish a republican form of government, which is currently designated as the Sixth Republic.

The political turbulence in Brazil has had a significant impact on the country’s economic policies and development, contributing to a highly fragmented Brazilian economy since 1945. Despite periods of accelerated economic growth, such as from 1951 to 1960 (with industrial growth averaging 9% and compounded GDP growth exceeding 7%) and from 1968 to 1973 (with industrial growth at 13.1% and GDP growth at 11.1%), economic crises exacerbated by political instability resulted in the premature removal of Brazilian leaders before effective solutions could be implemented.

The long-standing issues of accumulated inflation since colonial times and high external debt have persistently plagued Brazil. From 1981 to 1992, Brazil experienced a meagre increase in GDP growth of only 2.9%, accompanied by a 6% decline in per capita income. Meanwhile, external debt increased from 100% to an unprecedented 2000% by 1992, accompanied by a staggering inflation rate of 2700% during the same period. This period of ten years is commonly known as Brazil’s “Os Anos Perdidos”. Consequently, Brazil was confined to the “middle-income trap,” facing intensifying economic difficulties over time.

Indeed, Brazil made considerable efforts to stabilise its economy. In 1994, the government implemented the currency reform, designated as the Plano Real, which fixed the value of the Brazilian real in relation to the US dollar. This measure resulted in a notable reduction in the inflation rate, which declined from an alarming 2000% to 20% within a relatively short period. However, the reform had an unintended consequence: it led to a persistent decline in Brazil’s international competitiveness, resulting in reduced exports and fiscal imbalances. Consequently, the government was obliged to rely on external borrowing from international financial institutions in order to maintain economic stability.

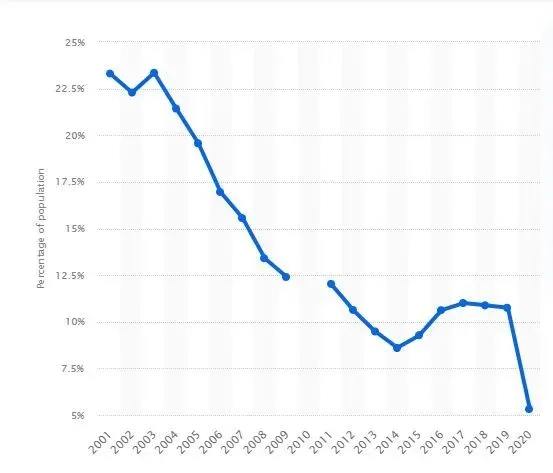

In the early 21st century, Brazil was confronted with a number of significant challenges, including an unemployment rate that reached 11%, and a substantial proportion of the population living in extreme poverty (earning less than $3.20 per day), which accounted for 23% of the total population. Brazil’s GDP in 2003 was $509 billion, down 42% from $883 billion in 1997! In light of these challenging circumstances, Brazil required a capable leader who could effectively steer the nation out of this predicament with a sense of responsibility and foresight.

In 2002, following a series of unsuccessful presidential campaigns, Lula da Silva, leader of the Partido dos Trabalhadores, finally achieved victory in the presidential election. He was held in high regard by Brazilian society. During his eight-year tenure, the Lula administration was notable for fostering economic growth and successfully addressing numerous social issues. Overall, the Lula government has done three things right:

Firstly, he pursued a moderate reform agenda aimed at stabilizing the financial markets.

The candidacy of Lula da Silva, Brazil’s first left-wing president in forty years, prompted global financial markets to react with concern. George Soros has publicly expressed concerns, suggesting that a Lula victory could lead to economic instability in Brazil. Additionally, Western mainstream media posited that Lula might deviate from the neoliberal currency reforms implemented by his predecessor, Fernando Henrique Cardoso. Such a deviation could potentially result in a resurgence of inflation.

In the context of mounting anxiety among international creditors and global investors, four months before the election, Lula issued a “Letter to the Brazilian People.” He underscored the point that there were no miracles in the life of a people or a nation. “It is imperative that a prudent transition be established between our current circumstances and the needs of society.” He told the financial world, in a very clear way, that he would respect all past Brazilian loan contracts and fulfill the remaining obligations of the country.

Upon assuming office, he appointed Antônio Palocci, a proponent of neoliberal policies, as Minister of Finance. He also designated Henrique Meirelles, the president of Boston Bank and one of Brazil’s largest creditors at that time, as the president of the Central Bank. Lula assured Meirelles that he would have complete autonomy in formulating and implementing policies and administrative decisions.

In order to relieve creditors from anxiety, Lula was forthcoming in informing the IMF of his willingness to increase the fiscal surplus target from 3.75% to 4.25%. This initiative proved to be an effective means of alleviating creditor concerns.

Lula’s message was unambiguous: under his stewardship, Brazil sought not a radical economic transformation but rather a series of moderate reforms designed to safeguard economic stability. The core objectives were threefold: firstly, to control high inflation through elevated interest rates; secondly, to maintain a freely floating exchange rate system; and thirdly, to achieve a national surplus.

During Lula’s 96-month tenure, Brazil maintained the highest official interest rates globally, ranging from 6% to 12%. This effectively controlled inflation. Prior to 2002, Brazil experienced an annual price rate of 12.6%. However, during Lula’s first term (2003-2006), the average annual price rate declined to 6.3%. In his second term (2007-2010), the figure was further reduced to 5.2%.

Secondly, Lula accelerated exports and swiftly repaid the national debt while the economy was robust.

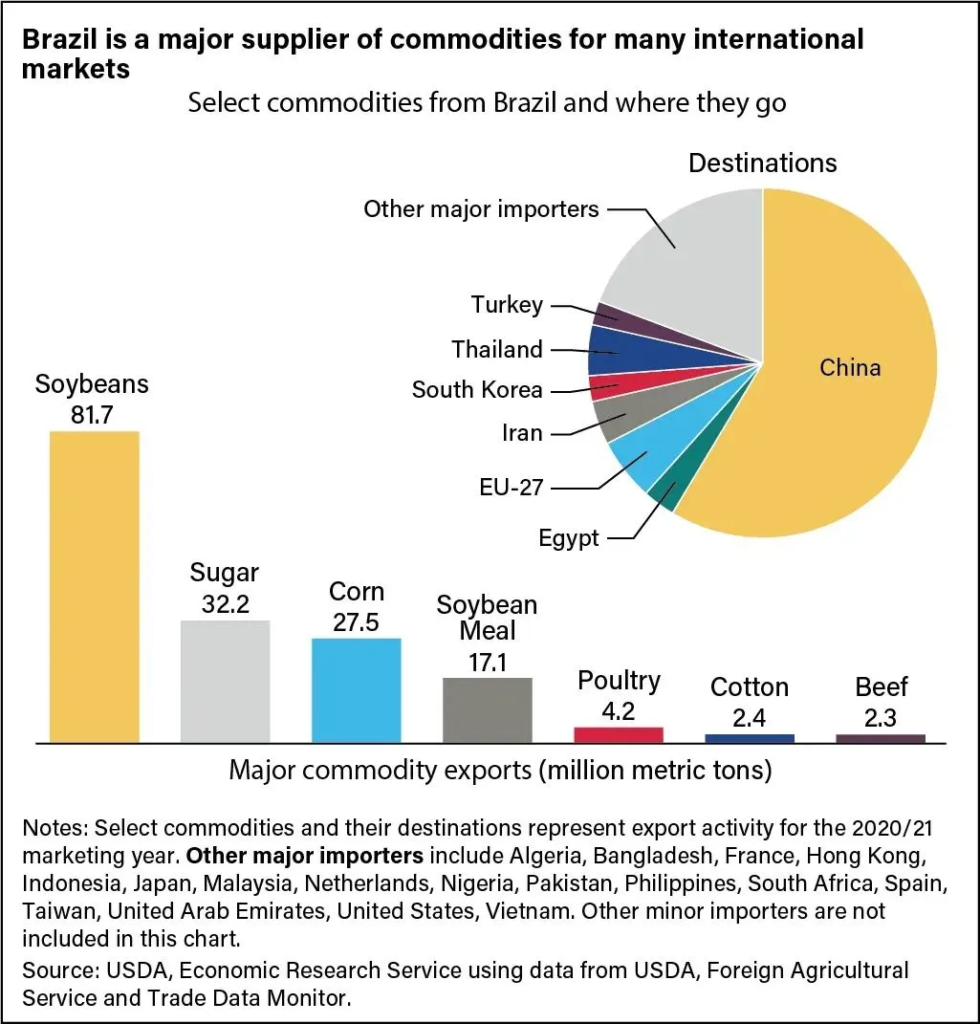

In the years following Lula’s ascension to power, Brazil experienced a surge in exports due to increased Chinese demand and rising international commodity prices, resulting in consecutive years of record-breaking exports. Brazil’s total exports were valued at $60 billion in 2002, but by 2006, they had reached $106 billion, and by 2010, they had exceeded $200 billion.

The increase in exports has led to a notable enhancement in Brazil’s capacity to repay international debt. By December 2005, Brazil had repaid all its international creditors, amounting to approximately $100 billion, which constituted over 40% of its 2010 GDP. Furthermore, the Brazilian government accumulated national reserves, with the value of these reserves reaching $86 billion by December 2006 and $290 billion by 2010.

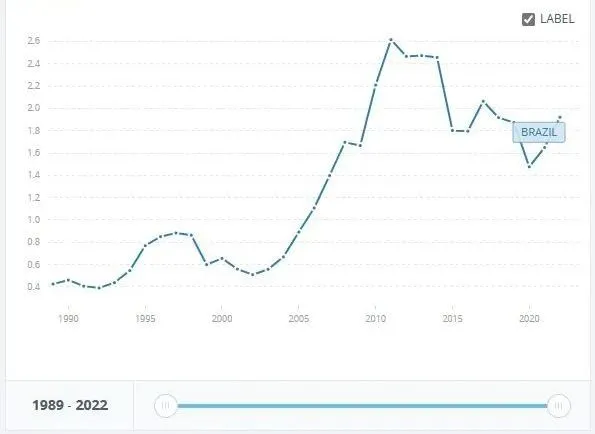

The expansion in exports also contributed to the growth of GDP. During the initial term of President Lula (2003-2006), the Brazilian GDP exhibited an average growth rate of 3.5%. In his subsequent term (2007-2010), the average growth rate was 4.5%.

Thirdly, in response to the financial crisis, Lula’s government decisively adjusted economic policies and reinforced macroeconomic regulation.

Lula is among the few political figures in Brazilian history who knew to be flexible in economics. In the context of the 2008 global financial crisis that swept across South America, Lula did not doggedly adhere to the principles of neoliberalism. Instead, he adopted a different approach, actively implementing Keynesian counter-cyclical policies.

On 30 March 2009, Lula published an article in the French newspaper Le Monde in which he offered a critique of the global economic crisis. Lula posited that while the crises of the past 15 years were those of Asia, Mexico and Russia, the current storm sweeping the globe had its origins in the United States, the center of the world economy. Furthermore, he stated that it was now necessary to reinstate appropriate policies and the role of the state. It is incumbent upon those in positions of authority to assume their responsibilities to society. While the safeguarding of banking and insurance institutions to ensure the security of deposits and social security is of significant importance, it is of even greater consequence to protect employment and stimulate production.

The solution proposed by the Lula government comprised the following measures: In terms of production, the government introduced tax reductions and fiscal stimuli with the objective of maintaining employment levels and ensuring the supply of goods such as automobiles and home appliances. To illustrate, the industrial products tax (IPI) policy saw the original tax rate for small cars reduced from 7% to 0%, while the tax rate for medium and large vehicles was halved. In terms of demand, the government introduced a series of investment and consumption loans, which were made available to businesses and consumers at preferential interest rates. The primary objective was to channel funds to the National Bank for Economic and Social Development (BNDES) with the intention of stimulating consumption.

The implementation of this series of measures yielded significant outcomes. Following a minor contraction in Brazil’s GDP in 2009, the economy exhibited signs of recovery the following year.

Furthermore, in order to further safeguard the well-being of lower-income populations and avert a considerable increase in the prevalence of extreme poverty, Lula introduced a range of social welfare policies:

– Firstly, the minimum wage was increased. In light of the fact that over half of Brazil’s formal employees and a significant proportion of informal workers receive the minimum wage, the government has taken the decision to raise this standard.

– Secondly, pensions and social security benefits were augmented. The government has given benefits equal to more than double the minimum wage to the bottom tier of retirees who depend on Social Security to survive.

– Ultimately, the scope of the “Bolsa Família” was expanded. This policy resulted in the extension of benefits to over 40 million individuals, representing 25% of Brazil’s total population. While the precise amount differed according to the composition of the household, the monthly stipend was set at a minimum of 15% of the minimum wage.

Lula addressed basic social needs and mitigated the recession’s impact on society by increasing the minimum wage, enhancing social security, and raising cash allowances. Consequently, in comparison to other Latin American countries, Brazil was less severely impacted by the global economic crisis of 2008. The proportion of the population living in conditions of extreme poverty decreased significantly, between 2003 and 2009, this proportion was reduced by nearly half to 12.5%.

This phenomenon correlates with the increase of a new middle class. By 2011, the proportion of the Brazilian population that constituted the middle class had reached nearly one-third, representing a more than doubling of the proportion observed in the 1980s. From 2003 to 2009, the middle class in Latin America exhibited a 50% growth rate. The study indicates that the middle class in Brazil was responsible for over 40% of the region’s total growth.

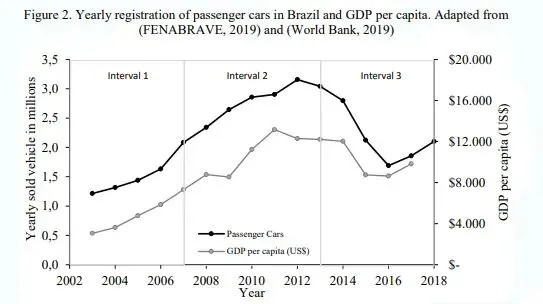

The growth of the middle class gave rise to the emergence of novel consumer demand patterns. To illustrate, travelling by plane, between July 2011 and July 2012, over 9.5 million Brazilians undertook their inaugural flight. Furthermore, there was a considerable surge in demand for motorcycles and automobiles. The annual number of new car registrations increased from 1.2 million in 2002 to 3.2 million by 2012, making Brazil the eighth-largest automobile producer globally.

Song Xin, the founder of Sinnvoll Consultancy, posits that Brazil’s ongoing economic reforms and achievements serve to illustrate the substantial potential of the country. Notwithstanding the considerable obstacles confronting Brazil’s economy, its vast market and resilient manufacturing sector bode well for its future growth and development, particularly in comparison to other Latin American countries such as Argentina. From this perspective, the decision of BYD and Great Wall Motors to invest in Brazil is driven by sound market logic and growth prospects, rather than by political considerations. Nevertheless, this evaluation is contingent upon the assumption that Brazil’s political and economic circumstances will remain stable and that the country will be able to effectively address the challenges posed by multinational automotive companies from Europe, the United States, and Japan.

Market Insights: The “Virtual” and “Real” Opportunities in the Brazilian Market

To ascertain whether Brazil has indeed evaded the “middle-income trap” and whether investment in Brazil is a more prudent decision, a comprehensive examination of the data reveals that the circumstances are not as simple as they may appear.

In reality, neither Lula nor his loyal protégé, Dilma Vana Rousseff (in power from 2011 to 2018), nor the far-right politician Jair Bolsonaro (in power from 2019-2023), often referred to as the “Brazilian Trump”, addressed fundamentally the challenge facing Brazil’s economy: structural distortions.

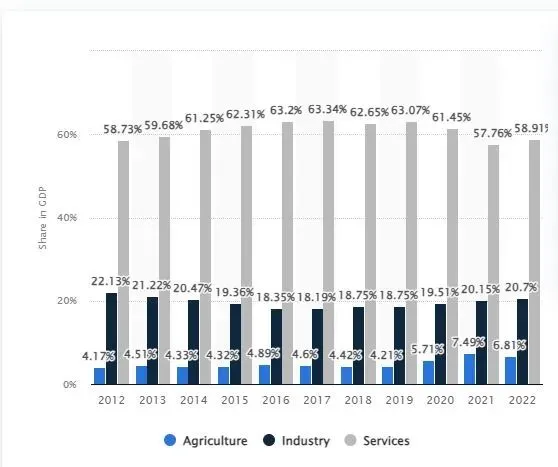

The specific manifestations of this issue include the following: low-value-added agriculture is experiencing a process of competition, the ongoing decline of technology-intensive and high-value-added industries, and the illusory prosperity of a finance-dominated service sector. Consequently, the Brazilian economy has been in a state of slow growth and recession since 2012. In contrast to the rapid economic growth experienced by India and China during the same period, Brazil has remained on the brink of recession, resulting in the country being labelled as having experienced a second “lost decade”.

It is an indisputable fact that agriculture plays an indispensable role in the Brazilian economy. Despite agriculture accounting for only 7% of Brazil’s GDP, if we add up the related agro-industry as well as the service sector, its broader impact reaches 21.4%, corresponding to 19% of the employed population. Furthermore, in terms of exports, agricultural products constituted 31.8% of Brazil’s total export value in 2022, thus representing one of the country’s most significant sources of revenue. During the presidency of Lula da Silva, it’s also the agricultural products that have opened up international markets and contributed to the renewed growth of the Brazilian economy.

In order to reinforce Brazil’s international competitive advantage in the agricultural sector, the Brazilian government has consistently enhanced support for farmers through a variety of measures, including direct financial subsidies, low-interest loans, and export incentives. Furthermore, it has bolstered agricultural research, with Embrapa (the Brazilian Agricultural Research Corporation) emerging as a leading entity in tropical agricultural research, significantly advancing agricultural productivity.

For Brazil, it is costly to maintain its position as a major agricultural exporter. On the one hand, the intense international competition, particularly from countries such as the United States, necessitates the continual increase in subsidies for agricultural products and ongoing investment in new technologies. Conversely, the low value-added nature of agriculture results in fewer jobs and economic activities being generated than those in industrial sectors. Consequently, the long-term return on investment in agriculture is very low.

The question of why Brazil has been unable to develop its industrial sector in a manner comparable to that of Asian countries is a topic of considerable debate.

In the past, Brazil has made considerable investments in the development of its industrial sector. During the military regime of the 1960s, Brazil’s industrialisation, driven by import substitution policies, was notably successful, with the industrial sector accounting for over 46.4% of GDP in 1984. However, from the 1980s onward, the misapplication of import substitution policies and the imposition of rigorous controls on the import of industrial products and emerging technologies—eben the forced seizure of foreign merchants’ personal computers—resulted in a decline in industrial growth. By the 1990s, while the economic sectors of developed countries had achieved a computer penetration rate of over 90%, Brazil’s rate was only 12%. Furthermore, Brazilian consumers were required to bear considerable costs for software of inferior quality, which constituted a significant obstacle to the modernisation of the Brazilian economy and the growth of sectors such as IT, the internet and artificial intelligence.

The industrial sector currently accounts for only 20% of Brazil’s gross domestic product (GDP), a figure that is less than half of its share in the 1970s. Furthermore, between 1990 and 2020, the value added by Brazil’s manufacturing sector as a percentage of GDP decreased from 14.6% to 10.2%. This reflects a sustained decline in the country’s industrial development.

The reasons for this decline are numerous and complex.

Firstly, it can be demonstrated that monetary factors play a significant role. The over-reliance on agricultural exports and the implementation of high interest rate policies have attracted a considerable inflow of international financial capital to Brazil. The floating exchange rate system has resulted in a sustained appreciation of the Brazilian real, which has had a detrimental impact on the export of manufactured goods and led to an increase in the import of foreign-made products. Due to the difficulty of competing with products from China and other Asian countries, many real industries have not increased, but rather reduced real investment.

Secondly, policy directions have also been a significant factor. Between 2003 and 2016, Brazil implemented three major industrial policies: Política Industrial, Tecnológica e de Comércio Exterior (PITCE), which aimed to drive institutional reforms; Política de Desenvolvimento Produtivo (PDP), which was designed to promote investment; and Plano Brasil Maior (PBM), which was intended to enhance value-added growth through innovation.

Despite their initial appeal, these policies do not, in fact, foster expansive industrial growth in any meaningful way. Rather than being driven by economic indicators, these policies prioritise social objectives, such as the dispersal of industries across different states, with the aim of achieving a perceived “balance”. With the existence of a plethora of tax incentives, a considerable number of industries have been observed to relocate from economically prosperous states to impoverished inland areas. Nevertheless, the results are evident: in the absence of industry agglomeration effect, the initial advantages were not maintained, resulting in the rapid decline of new factories.

Finally, there are institutional factors to consider. The Brazilian Constitution of 1988 espouses an extreme form of federalism, whereby sparsely populated states are afforded disproportionate representation in the two chambers of the National Congress, along with states with larger populations. The representatives of these states, which depend on agricultural production, are strongly opposed to industrial policies. This has resulted in challenges in the implementation of effective development policies and even the distortion of the government’s actions, leading to the formulation of industrial policies that do not align with economic logic. Consequently, Brazil has missed opportunities for industrial development.

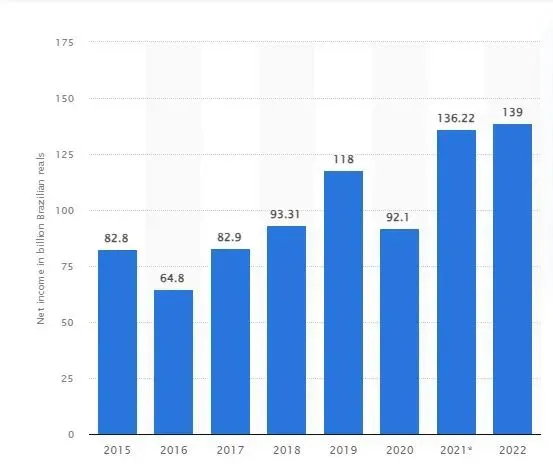

In Brazil, the rapid expansion of the financial sector stands in stark contrast to the stagnation of the industrial sector. Since the 1990s, successive Brazilian presidents have implemented highly liberal financial policies. Even those administrations with a left-wing orientation have, for the most part, pursued strategies designed to satisfy international financial capital, rather than to foster domestic economic transformation.

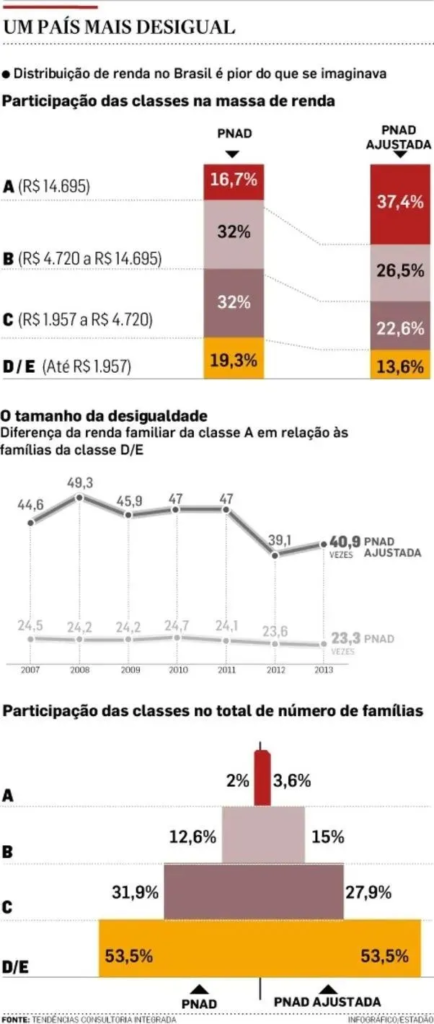

In 2005, the Brazilian Congress passed bankruptcy amendments stipulating that labor, as well as the state, would be the first to be held liable in bankruptcy cases, rather than banks and multinational corporations. Furthermore, the Lula government facilitated the privatisation of the reinsurance industry, thereby creating significant opportunities for international financial institutions. Thanks to these initiatives, the Lula administration succeeded in reducing the disparity between the wealthiest and poorest 10% of the population, and in improving the Gini coefficient. Nevertheless, a considerable degree of wealth concentration remains evident within the top 1% of the Brazilian population.

The considerable degree of opening up in the financial sector has facilitated the attainment of unparalleled profitability. In 2022, the Brazilian banking industry achieved a historic high income of 139 trillion Brazilian reals. There has been a notable increase in the consolidation of capital within large financial conglomerates. Notwithstanding the imposition of substantial service fees by banks, the government has not implemented measures to incentivise service enhancements or cost reductions. During Lula’s eight-year tenure, the federal budget allocated up to $600 billion to the financial system and Brazil’s elite, a sum that is ten times greater than that allocated for projects aimed at benefiting low-income groups.

For Chinese companies, in the face of the complexity of the situation, our more direct question is: BYD, Great Wall Motors, Leapmotor and even CATL to invest in Brazil in the end is it reliable? It should be said that the overall answer to this question is yes, but it is not a mega-positive and absolutely certain opportunity.

From a demographic perspective, Brazil has a population of 203 million, which positions it as the seventh most populous country globally and the second largest in the Americas, after the United States. Currently, Brazil exhibits a relatively youthful demographic profile, with a median age of 33.6 years. Nevertheless, projections indicate that by 2050, all age groups under 60 will less than the elderly population in terms of numbers. This demographic transformation reverses the population pyramid, influenced by a decline in birth rates and an increase in life expectancy.

The experience of “aging before becoming wealthy” has become a prevalent and cruel phenomenon in Brazil, and the other phenomenon is the country’s significant wealth disparities. Although the gap between the richest and poorest classes in Brazil has narrowed in the last two decades, thanks to a series of pro-poor policies, the richest 2% of the population still enjoys the lion’s share of society’s resources and holds the absolute wealth. This can be seen in the great disparities between the East and West of the country, as well as between the North and South.

Nevertheless, even among those in the middle class and lower-income brackets, consumer demand remains robust despite the constraints imposed by inadequate purchasing power. A study conducted by FGV EAESP has revealed that consumer borrowing in Brazil has reached a relatively high level. Since 2016, there has been a notable increase in the volume of personal loans, reaching a level that represents approximately 23% of GDP, which represents the highest historical level. This surge is largely attributed to Brazil’s prolonged economic downturn in recent years, which has diminished interest in investments such as real estate, prompting consumers to rely on high-interest consumer loans to meet their lifestyle needs. The rapid expansion of e-commerce platforms in Brazil in recent years provides further evidence of this trend.

In contrast to the prevalence of consumer desires, the ability to repay debts presents a distinct challenge. A study conducted by the American firm PYMNTS revealed that, in 2023, 25% of Brazilian adults encountered difficulties with defaulting, representing an 18.4% increase from the previous year (2022). A more troubling development is the fact that these defaults have now begun to spread to the corporate sector. The study indicates that only 25% of small and medium-sized enterprises maintain sufficient cash reserves for a period exceeding 60 days. Additionally, approximately one-third of entrepreneurs rely on personal credit cards to sustain business operations. A mere 17% of businesses are able to secure financing from banks. This might also be one of the important market factors that worry European, American and Japanese car companies.

Finally, it is also important to recognise the practical challenges that were encountered during the localisation process in Brazil. Mr. Li, a regional manager of a company with extensive operations in Brazil, identified three primary institutional challenges that foreign companies encounter during the localisation process. These are complex tax regulations, overly protective labour policies and an inefficient administrative system due to corruption.

Let us begin by examining the tax system. Brazil operates under a federal system, whereby its 26 states maintain distinct tax regimes, encompassing in excess of 60 different tax types. Research conducted by IBPT indicates that the financial burden associated with tax compliance for businesses exceeds 1% of turnover, representing a substantial obstacle for multinational corporations investing in Brazil. In December 2023, the Brazilian parliamentary approved the Tax Reform Act, which will be implemented in eight years, commencing in 2026. The new legislation introduces a dual VAT system comprising federal and local taxes, which will replace the current arrangement of five parallel consumption taxes. Moreover, the government is in the process of transitioning the tax collection model from the production side to the consumption side, with the aim of mitigating overlap. However, it is anticipated that the full implementation of this model will span a period of 50 years.

Then, with regard to labour protection policies, a noteworthy feature of the Consolidação das Leis do Trabalho (CLT) is that it grants workers and trade unions the right to collective bargaining. Collective agreements are afforded greater legal weight than individual employment contracts. This enables new standards established through collective bargaining to supersede existing employment agreements and directly impact subsequent contracts. The regulations, originally designed to safeguard vulnerable groups, have manifested differently in practice. In order to mitigate cost fluctuations, businesses increasingly opt for sem carteira assiada (informal employment contracts). This approach allows for flexible dismissals and hourly payment without adherence to minimum income and working hour regulations. Consequently, the number of formal contract employees in Brazil continues to decline, while the informal sector is experiencing a notable increase in the number of gig workers. It is evident that this system is detrimental to the interests of employers and inadequate in protecting the rights of workers.

Finally, an analysis of the issue of corruption in Brazil will be presented. In South America, corruption is not merely a challenge; rather, it is a pervasive norm. According to global corruption statistics from Trading Economics, Brazil has improved its ranking from 106th in the world in 1995 to 94th in 2022. However, it remains positioned towards the lower end of the global ranking. The fundamental causes of Brazil’s entrenched corruption can be attributed to two primary factors. Firstly, historical inequalities stemming from colonialism have resulted in bribery becoming the only avenue for resource access and gradually becoming entrenched in societal norms. Secondly, Brazil’s fragmented development trajectory, which has transitioned from colonial exploitation to modernization influenced by European and American paradigms. This disparate development has resulted in the emergence of disparities across economic, social, and political structures. The lack of humanism and openness to new ideas within the nation results in an absence of effective self-correcting mechanisms, which frequently leads to inefficient development and hinders the resolution of fundamental issues such as corruption.

In addition to the aforementioned challenges, it is imperative to consider the pervasive nationalist sentiments within Brazilian society. The legacy of colonialism has fostered a culture of distrust and caution towards outsiders, while the persistent actions of far-right groups could potentially exacerbate these underlying issues to a critical point in the future. This scenario has the potential to have significant and extensive implications for foreign enterprises operating in Brazil.

Returning to the automotive industry, as previously mentioned, the Brazilian automotive market is characterised by a notable phenomenon. While the motor vehicle market has exhibited consistent growth from 2012 to 2022, traditional automotive giants that entered the market in its early days have chosen to exit in significant numbers. This includes Ford’s plant closure and withdrawal from the Brazilian market in 2019, as previously discussed, as well as Mercedes-Benz’s sale of its plant to Great Wall Motors in 2021, Toyota’s closure of its plant in April 2022 and Volkswagen’s shutdown of its production lines in June 2023. Additionally, the Chinese company JAC Motors ceased operations at its plant, while Chery terminated the operation of some of its production lines in 2022 due to operational challenges.

It can be stated with a reasonable degree of accuracy that the Brazilian automotive market has reached an unprecedented low point. Despite an annual production capacity of 4.5 million vehicles, the industry produced fewer than 2 million vehicles in 2023 as a consequence of the significant reductions in production undertaken by major manufacturers. The sector has experienced a decline in employment of over 30% over the past decade. Should the current production crisis persist, it could result in the loss of 1.2 million jobs.

Upon returning to office in 2023, Lula initiated the “Carro Popular” programme, which was designed with the objective of revitalising the automotive industry. This initiative comprises substantial subsidies to manufacturers with the objective of reducing car prices and accelerating the approval process for consumer loans, thereby facilitating lending. These measures resulted in a partial recovery in Brazil’s automotive sector by mid-2023. However, despite these efforts, in January 2024, General Motors, Hyundai, and Stellantis (owner of Fiat, Jeep, Peugeot, and Citroën) announced the closure of their production lines in Brazil. This strategic decision reflects their attitude of the Brazilian and broader South American consumer markets.

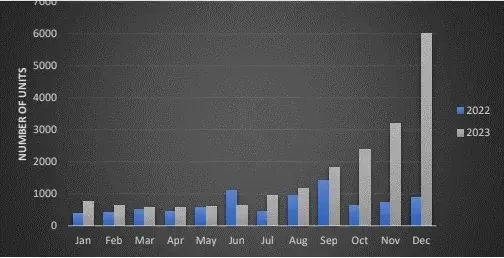

Chinese new energy vehicle companies encounter obstacles in the Brazilian market, yet they also possess distinctive advantages at this time. In terms of market performance, while Brazil’s pure electric vehicle market share was only 0.5% in the first half of 2023, there was a notable increase in the latter half, particularly in December with sales reaching 6,008 vehicles. At present, the market share has risen to 3%, reflecting a remarkable year-on-year growth of over 700%.

It is appropriate to acknowledge the achievements of BYD. As BYD’s manufacturing facilities continue to expand their geographical reach, competitors have been compelled to reduce prices, influenced by the pricing of BYD’s flagship Dolphin model, which is approximately $30,385. Moreover, the ongoing localisation efforts of Chinese automakers have resulted in increased recognition among consumers.

Moreover, from a broader perspective, Chinese companies benefit from two significant advantages when investing in Brazil: geopolitical stability and strategic platform advantages. As Brazilian scholar Maurício Santoro has observed, these advantages are of great consequence for Chinese enterprises. Firstly, investment in Brazil serves to assuage concerns pertaining to geopolitical tensions, which are more prevalent in markets such as the United States, Canada, and Europe. Secondly, Brazil’s geographical location within South America makes it an optimal hub for Chinese companies seeking to expand their reach into neighbouring countries, such as Argentina and Chile.

For Chinese companies, Lula’s rise to power seemed to have laid the political groundwork for a big push into the Latin market. Lula’s political fate also seemed to be closely linked to China. Brazil initially benefited from China’s rapid growth in bulk import demand when Lula first assumed office in 2003, which led to a period of rapid expansion. Two decades on, Brazil is poised to benefit once more from China’s rapid advancement in new energy vehicles and its urgent external expansion requirements. Alexandre Baldy, the head of BYD Brazil, has stated that the country has the potential to transform its natural resources into cutting-edge industries, thereby establishing itself not only as a country with a promising future, but also as a country with a strong presence in the present.

Song Xin summarized the situation as follows: Viewing Brazil globally, it is a country with a vast market yet challenging for achieving substantial success. The strategic decisions made by BYD and Great Wall Motors indicate that Brazil basically aligns with the criteria sought by Chinese companies targeting global markets. Chinese enterprises have ample opportunity to capitalize on their cost-effectiveness advantages in this market, with localization and precise operational capabilities emerging as pivotal factors in establishing a strong presence in Brazil.

The complexity of the Brazilian market requires extreme caution on the part of Chinese companies. It would be unwise to ignore the potential risks that arise from Brazil’s historical context and distinctive political and economic traits. It would be prudent to adopt a strategy that is both prudent and conservative, with a focus on steady advancement. While securing market share in mid-to-low-end segments is of significant importance, sustaining profitability is of paramount importance.

In conclusion, the future success of Chinese automotive companies remains uncertain. While a positive outlook is maintained, an excess of optimism can result in significant failures. The decisions of European, American, and Japanese car manufacturers to exit the market were based on rational assessments. Similarly, it is imperative that we address the challenges with a realistic outlook.

Reference:

1.From Pero Vaz de Caminha’s letter to the King Manuel I.

2.Testing the limits of China and Brazil’s partnership, Harold Trinkunas, 20/07/2020, BROOKINGS

3.Investing in the Pan Amazon: How China’s investment operates, 04/10/2023, Timothy J. Killeen, Mongabay

4.What Is the State of Chinese Investment in Latin America?, 08/09/2023, The Dialogue

5.China makes a big bet on electric vehicles with Brazil investment, Sam Cowie, 20/07/2023, Al Jazeera

6.Shein estreia à frente de grandes nomes entre as maiores do varejo brasileiro, mostra estudo, Lorena Matos, 17/08/2023, MoneyTimes

7.Shein abre loja física temporária no Brasil; veja onde, quando e como garantir entrada, Lorena Matos, 11/12/2023, MoneyTimes

8.Temu, ainda não lançado no Brasil, já possui mais de 221 mil acessos e concorre com Shein, 16/10/2023, e-commercebresil

9.A Raiz das Coisas. Rui Barbosa: o Brasil no Mundo, Carlos Henrique, 2007, Civilização Brasileira

10.Evolução do carro de passageiros brasileiro de 2003 a 2018: tecnologia, preço, emissões, mercado e política, Fernando Wesley Cavalcanti de Araújo, 2023, REVISTA OBSERVATORIO DE LA ECONOMIA LATINOAMERICANA

11.Industrial policy as an effective development tool: Lessons from Brazil, João Carlos Ferraz, David Kupfer and Felipe Silveira Marques

12.Au-delà de la récession, nous sommes face à une crise de civilisation, Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva, 31/03/2009, Le Monde (Paris)

13.Nossas exportações: opção política ou vocação natural?, Paulo Kliass, 29/11/2001, Carta Maior

14.40% of Brazilians at Risk for Debt Defaults, PYMNTS, 28/05/2023

15.Lula’s Political Economy: Crisis and Continuity, Paol Kliass, 12/05/2011, nacla

16.Brazil and ‘Latin America’ in Historical Perspective, 02/05/2010, Youtube

17.Au Brésil, le président Lula tente de faire redémarrer l’industrie automobile, Anne-Dominique Correa, 23/08/2023, Le Monde

18.Lula’s playbook: Brazil bets on a return to state capitalism, Michael Pooler, Bryan Harris, 16/01/2024, Financial Times

19.‘Parte 2’ da reforma tributária pode tirar do Brasil posto de país mais Desigual, Redação RBA, 24/12/2023, Rede Brasil Atual

20.BEV Sales Shoot Past All Expectations in Brazil in December, Rise 700%!, 22/01/2024, Clean Tec